The first in a new series of posts memorializing— continuing—my lifelong conversation with my father, who died in 2019. And who taught me to do it.

Oh Hi, Dad

You know the Guy Clark song about his father’s death? “The Randall Knife?” If you don’t, stop reading, click the link. Come back when you’re ready.

Able.

My dad wasn’t like Guy Clark’s. I don’t know that he was wise (except in pretty much everything about the way he approached being alive). Randall knives—weapons of any kind—were not his thing. But if they were, I wouldn’t have had to sneak one out of his drawer. And I wouldn’t have gotten in trouble for breaking off a piece trying to jab it into a tree trunk, because he would have been out there with us, inventing rules for the game. Very possibly trying trick-sticks. Throwing behind his back, or using only his feet.

He did value some material things, his stuff, but for what it was, not its name or symbolic status. That is, he liked towels when they were soft, or warm from the sun. He loved—loved—his stereo speakers for what they helped music do to him when he sat down and listened, which was as often as possible. He loved beautifully designed things, but to use, not to look at. A pencil that felt right in his hand. A knob with a satisfying click.

The dining room chairs were an exception. Those, the look just got him, I think. We still need to have a chat about those chairs, Dad.

Wish we still could. Every day, I wish that.

We never would have, though. What my dad and I talked about, pretty much every single time we talked—every moment life left us alone to get on with talking—was what we were reading. Listening to. Going to see. Watching. The wonders we’d found that other living things had created with their allotted time.

Very occasionally, we talked about the wonders we were trying to create. His paintings, designs, music. My words (and sometimes music). Mostly, we discussed the struggles seemingly built into the process of creating. The inevitable and crushing and weirdly satisfying failures.

He was such good making-art company, my dad.

He was the best appreciating-art company.

The best.

Three years after his death, my mother is selling their house. Which is right, and good. Last time I was there, she asked me if there was anything of his that I wanted.

In “The Randall Knife”, the singer-narrator goes for the thing his father haunts. But my dad never haunted anything—too busy living—and if he were (is?) here today, he wouldn’t bother doing it now, either.

Too much still out there to hear and see and discover and drink in. And create.

Which is why, when my mom asked, I went for his notecards.

Since his death, up until now, I’ve only written directly about my father once, in a piece of short fiction called “Over” that wound up in the Michigan Quarterly Review. I talk some about the notecards there.

Like I said, my father never haunted anything. But these cards haunt me. And it appears I’m not done writing about or discovering them yet.

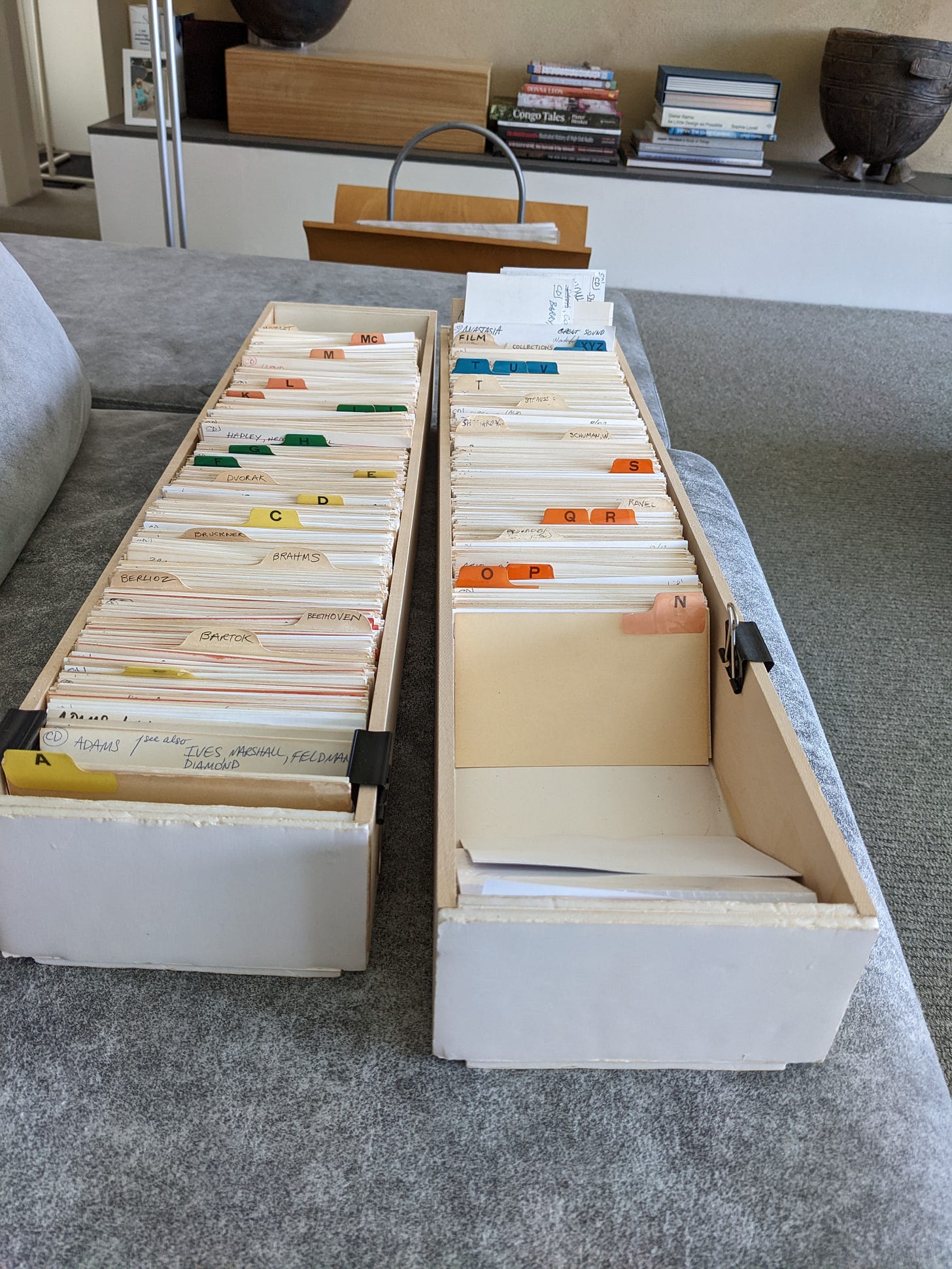

What even are they? Not one thing, I don’t think. A library catalog, in part, for sure (my dad loved libraries, as much just to be in as to check out from). There’s one for most of his records and CDs (almost all of them classical). A few for movies, none for the books. Sometimes, all that’s on them is database information. Label, orchestra, pieces, conductor, featured performer.

Sometimes, in the upper right corner, there are ratings. He apparently tried several different systems during his collecting and cataloging life. Meaning, his whole life.

On some cards, he uses numbers. On others, stars. On some, there’s a sort of squiggly splotch. I’m still not clear if those are ratings.

Not all of the ratings are even his; my dad had a lifelong, endearingly childlike respect for institutions heralded (if only by themselves) as critical authorities of record. A “Rosette” in any edition of the Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music for one of his favorite recordings could trigger sounds from his throat more akin to paroxysms than language. He really only bothered learning to use online search engines so he could track down discs that got raves in Fanfare or Gramophone.

Which doesn’t mean he always agreed with those publications. Because my dad also had a lifelong, endearingly childlike urge to fling water-balloons at authorities of record. Some of my favorite notecards refer to comments by Penguin or Gramophone declaring some new recording as the incontrovertible new standard of something or other. Followed by my dad’s response, often in capital letters, usually with exclamation points: “NOT by ME!!!”

And now, here they are, on my desk. Flipping through them, I hear his voice. See his face. They capture the force of him, more than any photograph. Possibly more than any of the cars he designed or the art he painted. But doing only that—flipping through, remembering, treating this collection as a memorial or centerpiece in my personal museum to my father—feels like an injustice. Or worse, a waste.

It isn’t what he would have done with them.

Did.

So I’m thinking I’ll go on talking to them instead. To him. My plan is to pull cards from these stacks. Elucidate and enjoy them. And then respond with somehow relevant or consonant discoveries of my own. Things I would have shared or did share with him. Half-baked ratings, paroxysmic gurgles, inexplicable tangents, (possibly embroidered) anecdotes, the lot.

In other words, fuck haunting. Fuck honoring memory. Definitely fuck dying.

Hiya, Pop. What’cha got today?

"But my dad never haunted anything—too busy living..."

Our parents had that in common. When my mom turned 65, I bought her one of those Record Your Memories prompt books, hoping she'd write about her life so that her grand- and great-grandkids would know how amazing she was. She never slowed down enough to answer a single question. When my sister & I were cleaning out her apartment after her death, I found a folder neatly labeled "Arrest" and the year (I've forgotten but she would have been in her late 50s/early 60s). Inside was her charge sheet from her Civil Disobedience arrest. Sadly there was NOT a copy of the picture I'd seen, years before, of her being led away in zip-tie cuffs, but that lives too vividly in my memory ever to fade. I have that folder now, to remind me that her legacy was a world she worked tirelessly to make better. And though she doesn't haunt me, the older I get, the more likely I am to see her face when I look in the mirror.