Personal Savior (Pt.1)

from ALL HAPPY PEOPLE

A winter’s tale. For, you know, winter…

This is another from my ALL HAPPY PEOPLE series, focusing on Shannon, the most elusive and impactful of Z’s romantic partners.

The original idea for this one pre-dates ALL HAPPY PEOPLE by a good twenty years. I liked it then, but knew I’d made a mess of it. I’ve tried it half a dozen times since, but I could never nail it down. The breakthrough came when I realized that, in her way— which probably isn’t yours and hopefully isn’t mine— Shannon is indeed a happy person. At least within the parameters of this project.

I rarely write fiction about writers, because frankly, I’m more interested in what they write. But this story draws at least some inspiration from my grad school days in Missoula, Montana, which were almost certainly the most collegial of my pre-teaching writing life. The time I came closest to feeling part of a community of writers, at least until I set about making one. Which is funny, really. The Missoula in this story (as well as the one I lived in, I suspect) is a place I half-dreamed. I never quite fit as a proper Montana MFA writer—then or since— and yet I briefly felt at home there. The university gave me some financial support and chances to teach; my peers and professors and mentors let me play on the softball teams and write for the newspapers and magazines, offered input, let me roam. What more can any young artist realistically ask?

One final note: I’ve never understood that thing about resemblance to persons living or dead being coincidental. All good characters bare resemblance to persons living and dead. What good are they if don’t? But no one here is anyone I knew, not even in disguise.

The storm that rolls through this story, though…that’s real, and I’m actually underplaying it. It was a whole lot colder.

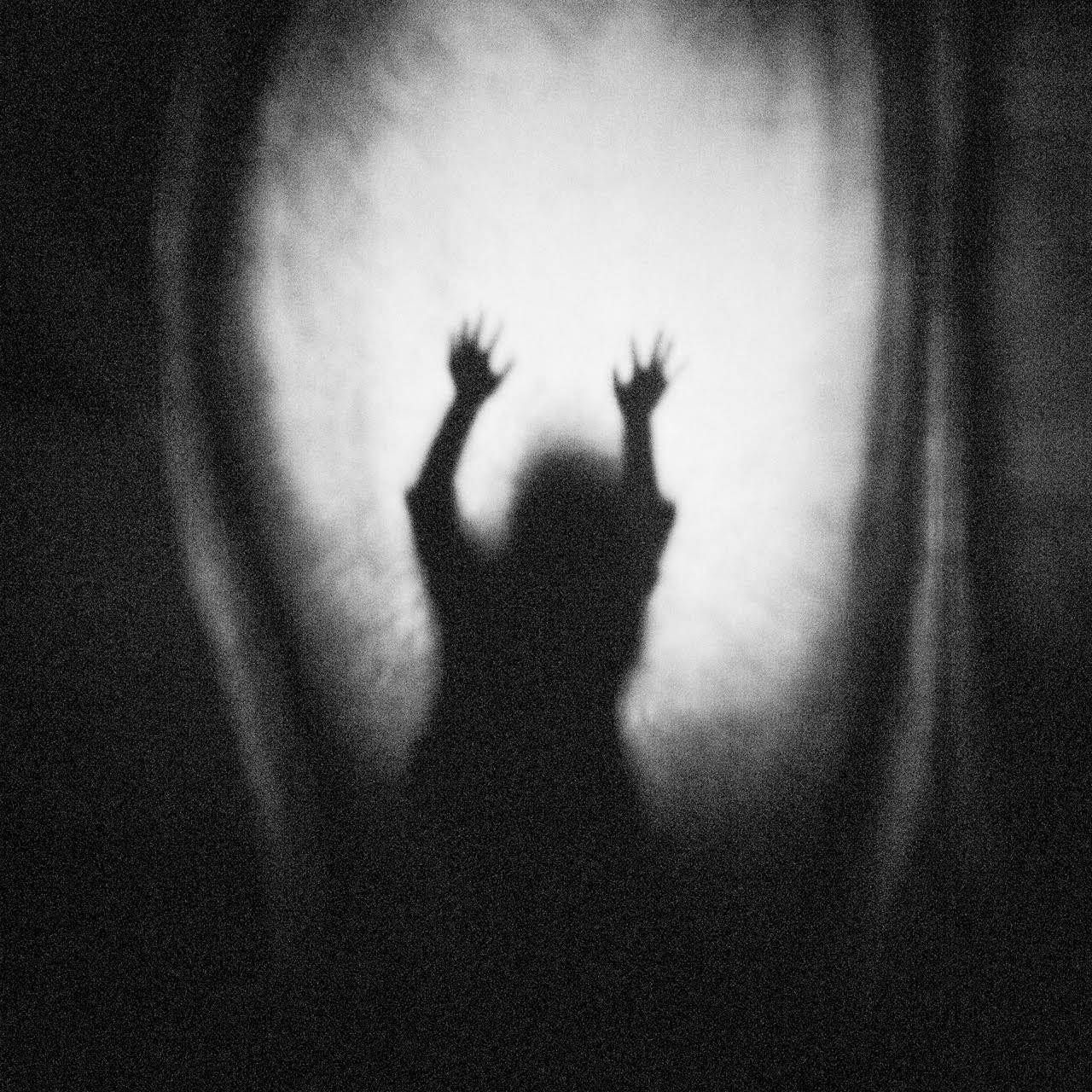

Once again, an insufficient thank you to Jonas Yip for the dazzling cover image.

Pt. 2 next week…Personal Savior (pt.1)

On the day her divorce from the Mess became final, Shannon decided it was probably time to move out. By the end of that dreary, early-December afternoon, she’d rented a front-corner one-bedroom in the Martha, a crumbling, shingle-and-drywall hulk originally built by the University of Montana in the 1920s to house pregnant single women whose families had disowned them. Later, it became Missoula’s most infamous hippie commune. The threadbare yellow carpeting still reeked faintly of pot or maybe just mold. The downstairs hallway walls bore fading murals of trout leaping from a meadow stream, wowing an audience of applauding grizzly bears in polka-dot bowties. One of the grizzlies’ mouths was obscured by a white splotch, as though someone had beaned it with a snowball.

That evening, back home, Shannon baked a lasagna, and she and the Mess ate together by candlelight in the silent little bungalow shaded by twin ponderosa pines where she’d originally thought they’d stay six months, tops, and then—as recently as last summer—assumed they’d live for the rest of their lives. Neither of them spoke, and the Mess spent most of the meal hunched forward, flop-curls and three-day stubble obscuring his face, forearm encircling his plate as though protecting it from other prisoners.

“Oh, come on,” she finally said. “Don’t look so sad.

“Don’t look so not-sad,” he mumbled, pulling a mozzarella string free of his teeth.

“I’m sad,” she said quietly.

“Me, too.”

They both had seconds, though. The Mess had thirds. He took his time scraping the last crusted noodle and cheese bits off his plate. Even when he’d finished, he stayed hunched.

“Go finish packing,” he said. “I’ll clean up.”

She couldn’t help it. She snorted.

“Unfair, Shannon.”

“The Mess cleans up.”

“Once again, you have willfully misused—have in fact perverted—my name.”

For the first time all night, Shannon really did feel sad. Or rather, for the first time that night, her sadness stung. “You know what? I didn’t pervert or misuse. I actually forgot.”

“Well that makes it a whole lot better. Thanks.”

Before she could apologize or remonstrate, he looked up, and there was his little boy bear-grin. “It is the fate of my kind. To be forsaken and forgotten.”

“Poor Mess,” Shannon said, and meant it. Almost, she reached out to take his hairy hand, then realized that was the real reason his forearm had stayed in front of his plate the whole meal: he’d been hoping she would. Which annoyed her. Which really wasn’t fair.

She made herself touch his arm. It felt too warm, as though he had a fever.

He nodded. The nod, she knew, was a thank you, which made her sad all over again. The sweeter, less stinging sad, though.

“-iah,” he said.

“Poor Messiah,” said Shannon.

“Better hurry. The Huckleberrys will be here any minute.”

“Urg.” She got up, automatically gathering dishes. “Why did you call them?”

“They have a truck.” He was staring down at the tomato sauce splotches where his plate had been instead of getting up to help.

“They’re just going to come in arguing. Why do we have to have both of them?”

“They come as a set. And they actually wanted to help.”

There it is again, Shannon thought. Never in her life had she felt so prone to saying the wrong thing as she had during her four-year marriage to the Mess. Before that, she’d actually thought herself remarkably graceful in that way, good with words out loud as well as on the page. Maybe there were simply too many wrong things one could say to the Messiah.

God, she hoped that was it.

“I’d just like our last night to be argument free,” she said, trying for gentle but hearing the distraction she knew he heard.

“That’d make it like the rest of our nights.”

Shifting the plates, Shannon gestured with her chin. “You have cheese under your nose.”

“You sure it’s cheese?”

“Remind me how I’m perverting your name?” said Shannon, ducked free of his gaze, and slipped into the kitchen.

It really had been the exact opposite of her years with Z, she thought. With Z, saying wrong things had seemed almost impossible. So much so that she’d started to wonder whether she was saying anything at all.

By the time the Huckleberrys arrived, she’d fled for the back bedroom to pack her laptop and tape up the last few book boxes. Just as she finished, Fin Huckleberry appeared in the doorway, calling something over his shoulder to his brother that sounded like, “You fish it, then.” Shannon didn’t ask, and he didn’t offer, just stooped for book box number one. LIT A-F.

Abruptly, though, he looked up from under his Ospreys! cap. With his dark eyes and ruthlessly shaved, baby-pink skin, he looked like a stray dog shorn for mites.

“This old?” he asked.

“What?”

“’LIT A to F. Does that apply to what’s in this box, or is it from an old move? I’m just curious.”

Strange man, Fin Huckleberry. Much the more interesting of the brothers. Occasionally the creepier one.

“Both,” Shannon finally said, an uncomfortable smile shivering over her mouth. “It’s the same box.”

“From when you moved here. From New York.”

She nodded.

“And it’s still Lit A to F.”

“Could we just go, Fin?” she murmured.

“Sorry.” He hefted the box. “That just weirdly seems like something I would do.”

Yes it does, she thought, not liking it, and threw herself more determinedly into final packing and carrying.

Into the bed of the Huckleberrys’ truck went her laptop case, nine boxes of books, the futon the Messiah hated because he claimed it gave him “levitation dreams,” the pots, and pans because the Messiah sure as hell wouldn’t use those, the plates—not for the same reason, she hoped, just because they were hers—some folding chairs, and the century-old student desk she’d bought for seventy-five cents at a yard sale the weekend she’d moved into this house. Something about the roughness of that desk still fascinated her: the play of light over the grooves and overlapping grains in the cheap pine, and the warps in the work-surface that made anything she put there tilt but also held it fast, as though lodged in the Y of a good climbing tree.

A promising metaphor for a new marriage, she’d thought at the time. The evolving, subtle warps and grooves that hold and cradle you. Fortunately, she’d kept the thought to herself, because as it turned out, she hadn’t known shit about marriage. How could so much time infused with so much real, shared love wind up so mutually disappointing?

The Huckleberrys really were gentlemen, in their way, or else the Messiah was having one of his not so rare intuitive movements, because he convinced them to take his car and go home and let him drive their truck to the Martha alone. He’d had to bribe them with the remaining half of the lasagna, which was a serious sacrifice, Shannon knew. It was almost certainly the last not-takeout in the Mess’s foreseeable future. She drove the mile and a half up Higgins with her eyes in the rearview mirror of her Versa, watching the Mess watch her.

At the Martha, they decided to tackle the desk first, and as they worked it off the bed of the truck, Shannon almost wished the Huckleberry brothers had come, after all. She’d never had the desk weighed, but it was far too heavy for even the Messiah. It took them several minutes of struggling and grunting and swearing at each other to work it sideways up the front steps. The moon came out. The Mess flipped it the bird and leaned, panting, over the desk for another heave. He’d just bumped the front two legs onto flat porch when the man with one hand pushed through the Martha’s crooked screen door, saw them, stopped, and pulled the door closed behind him with his stump.

Shannon straightened, then had to throw her hips against the desk to keep it from sliding back over her. She watched the man move to the edge of the porch on the other side of the desk from the Mess. He wore a heavy, checked lumberjack shirt under an unzipped winter jacket, and blew breath through his nostrils like a dragon. He looked a little older than the Messiah, with blond curls that were going to stay blond a while yet and a jowly, prickly face. Casually, he draped his gut across the Martha’s leaning porch banister.

“Neighbor?” Shannon said, the desk pressing her pelvis. The Mess grunted and attempted to pull more of the desk onto the porch. The man in the lumberjack shirt blew another nostril-breath and gazed down at the Huckleberrys’ truck. The night breeze seemed to flow around him as though he were a lamppost.

“You’re in the front place?” He gestured toward the windows. Her windows. And there was that stinging sadness again.

She nodded. “Shannon.”

“Larry. Welcome to sanctuary.” His expression surprised her even more than the comment. His smile bore the fervent familiarity she’d always noted on the faces of students who volunteered to lead campus admissions tours.

“Want to get sanctuary’s door for us, Larry?” said the Mess, grunting again as he straightened.

“Have you accepted Jesus as your personal lord and savior?”

Deep in her stomach—for the first time in this whole, surreal day—Shannon felt actual anger bubble. She fought the feeling down. Whatever that was about, it had nothing to do with the man on the porch.

“Not tonight,” she said quietly.

“As good a night as any,” said Larry.

Across the desktop, Shannon eyed the Mess. The grin she sometimes loved even now spread over his face.

“Don’t,” she said. “Please? Leave him alone.”

Just like that, the Mess’s expression went surprised, then embarrassed, and she remembered why she really did love that smile when she did. For the Mess, the game was always engagement, pure and simple, even if his targets experienced it as provocation. Most of all, to him, it was a game.

With a heave, the Mess dragged the rest of the desk onto the porch, then shivered as a gust froze the sweat on his skin. He looked good up there with the gray ruin of the Martha rising behind him and the moon threading silver through his hair. This is how he’d seemed to her when she’d married him: a person actually capable of pushing the world around, but who knew it was going to push back. Hard.

Larry swiveled his gut toward the Mess. He blew another breath. The smile vanished from his face.

“You really aren’t going to get the door for us, are you, Larry?” the Mess said.

Tucking the hand on his good arm into the armpit of the other, Larry left his stump on the railing. “Have you accepted—”

“Well, they do call me the Messiah.”

Larry twitched. “Do they, now? Why is that?”

Shannon shoved her own end of the desk, bumping the legs into the Messiah’s.

“Ow,” he snapped, while she gave Larry a tried smile.

“Because he used to have a really long, stupid beard, back in his mountain man days,” she said. “Now we just call him Mess, for short.”

“That is not the origin of my name,” the Mess intoned, dropping into the cadence he’d refined over twenty-plus years of answering this question.

Shannon bit her tongue, closed her eyes. Then she realized this might be the last time she ever heard this recitation, which didn’t make her less annoyed, only more attuned. She bobbed her head to the rhythm.

As always, the Mess had fiddled with the words since whenever the last time was. He never quite wound up satisfied or got them exactly right, which was pretty much the story of his writing life. Also the story of why he barely had one, now.

“To my brethren on the Ladies of Kicking Horse Reservoir Softball Team (all-male, incidentally), I am He who crossed the Clark Fork, bringing championships and freedom from the tyranny of the once-invincible Rudolph’s Home-Churn Ice Cream team with my mighty swing and deceptive speed. To my awe-struck students in the world famous University of Montana nature and science writing program, I am He who leads them to language—”

“And teaches them to drink it,” Shannon couldn’t help muttering, but when the Messiah shot his grin at her, she looked away.

“To the Jews of Western Montana,” the Messiah continued, “I am He who led them out of the wilderness and into the promised basement of the Lutheran church over on Front Street for once-a-month Shabbat services. That your church, Larry?”

Pushing off the railing, Larry ignored the Messiah and looked at Shannon. “My door’s the one next to yours, end of the hallway. You too can receive grace. His Mercy is boundless.” He moved around the desk, down the stairs and away across the street in a cloud of breath.

Shannon pursed her lips as her stomach boiled again. “Thank you, Mess, for ensuring that my new life is going to be filled with the same neighborly good will as my current one.”

“Oh, come on. I just saved you from, minimum, three solid hours of proselytizing. Not to mention literature. I’ll bet you anything he’s got literature.”

“In his mind, he’s helping me. Saving me. You realize he was seriously offended, right?”

“People get offended too easily.”

“I’ll pass along your decree.”

The hurt look flitted across his face again, but this time Shannon held his gaze until he looked away.

The Mess stayed another hour, unrolling the futon, unpacking a few books and commenting on them. Near the end, half-sitting atop her desk, he stared out the window at the gas station convenience market down the block.

“Just…trying to see what you’ll be seeing,” he said.

She walked him out. At the bottom of the steps, he turned, looking pathetic. She crossed her arms against the intensifying cold and bit the inside of her cheek. “Oh, don’t be so sad. Go to Jim Huckleberry’s house and make up one of your games and drink. How about no-hands nine ball?”

That worked. The Mess positively beamed. “No-hands nine ball! How is it we haven’t tried that?”

“How indeed.”

“How is it you’re the one who dreamed that up? We’ll name it after you.”

“Not quite as beneficial for me long term, I’m thinking, as mercy or grace.”

“But more achievable, babe.”

“The words of a seriously humbled Messiah.”

She regretted that as soon as she said it, but the Mess neither flinched nor winced. He spread his arms to the frigid air. “Don’t know about that. This Messiah achieved you. For a while.”

“Me, too,” said Shannon. She felt dizzy now, and tired, and done talking. She wasn’t sure what either of them were saying anymore, but whatever it was felt dangerous. “Goodnight, Mess.” It’s been fun, sometimes.

He lowered his arms, turned away, turned back. “You coming to Northside next weekend? For Snowball Softball?”

“Softball in the snow with your ex in the opposing dugout. The Montana literary lady’s ideal.”

“Does that mean you’re coming?”

She unclenched her jaw, felt her face fall open and her tears well. So be it. Let him see. “Wouldn’t miss it.”

“I still love you, babe. For what that’s worth.”

“I still love you,” she heard herself say. “It’s worth exactly that.”