Well, that didn’t take long.

Two sentences into this, my second quarterly annotated music playlist, I fell into my own trap.

Right there at the top of my Don’t Bullshit Me post in November, I laid out a plan. You might have mistakenly thought that was some sort of user’s guide for you. It was actually a reminder and warning to myself:

“These round-ups aren’t criticism...Call them fan’s notes.”

The trap is that I like criticism. The good kind, the real kind, written by writers who love language and use it to dig into and argue about and make connections between and draw fresh meaning from and celebrate art worth discussing. I once made part of my living doing that. But I wanted these columns to be something more in keeping with the whole idea of this Substack. The whole happy-in-our-own-ways thing.

In other words, I wanted to use the language I love to dig into and argue about and make connections between and celebrate art worth...No, wait a second...

Oh, never mind. Here’s this quarter’s slate:

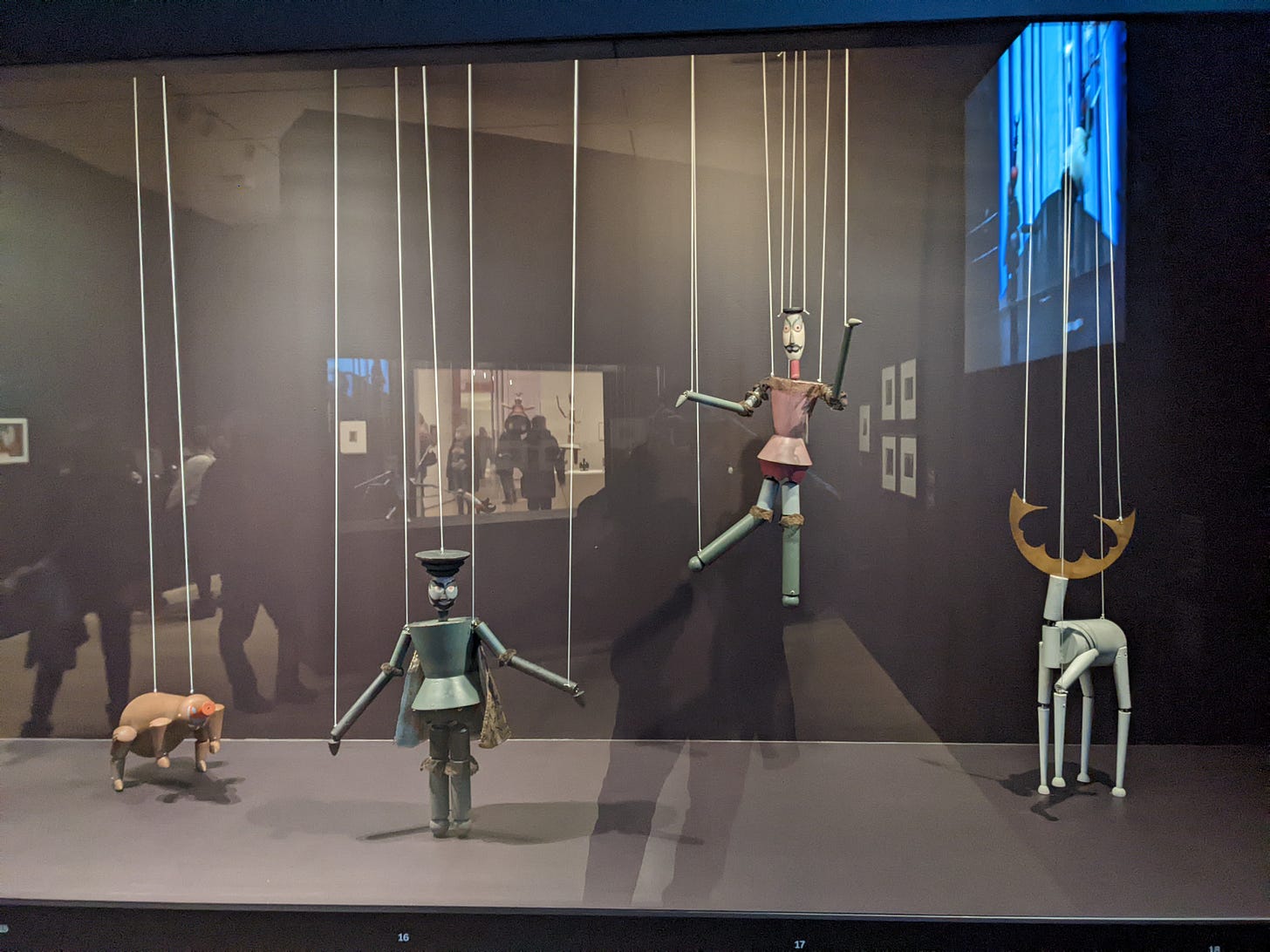

(photo is mine, of Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s stunning Dada marionettes at her current MOMA exhibit)

TINY BRAINS: THE FEBRUARY MUSIC ROUND-UP

HECTOR ZAZOU—Chez le Commandeur

I didn’t get to see the mighty Tuxedomoon during the era I fell in love with them. By the time I was old enough to get to the Bay Area on my own and visit friends and see middle-of-the-night shows there, the Moonies had already decamped to the older, more stylized demimonde in Belgium, where they’ve gone on making memorable music that only sometimes stirs quite the same delicious disquiet as those first few singles and records did (and do) for me. (I mean, if you’ve never heard “Dark Companion”, or “(Special Treatment for the) Family Man”, or “Crash”, which is mostly a Blaine Reininger solo track, I think, and which got me spooked by plane shadows long before we had a shared cultural association...).

I first found Hector Zazou’s music because the Tuxmoon guys shared a European label and some projects with him. I’m not even sure what made me put this on for the first time in years. Partly, I suspect, a sort of nostalgia for a world I really did believe was opening out in front of us all, was connecting itself to itself in species-saving ways.

Zazou’s concept was to juxtapose—the actual verb on the Bandcamp liner notes, fascinatingly, is “confront”—three prominent Congolese singers, Bony Bikaye, Kanda Bongo Man and Ray Lema—with classical musicians, then add his own graceful electronic flourishes and production touches, all as a soundtrack to a photo-novel he really did create.

I don’t know, maybe it feels like exploitation now. Pretention, too. Naiveté, maybe, especially in hindsight.

Except it’s so beautiful, both the sounds themselves and the audible listening that led these spectacularly gifted musicians to these sounds.

So I’ll call it hopeful. Still.

NO-NO BOY—The Best God Damn Band in Wyoming

You can keep your Succession, your Gilded Age. My personal American dream has always involved people making havens where they can generate and trade delight and meaning in the face of a world—meaning a society, as in all of them, ever, so maybe I mean a species—instinctively opposed to (or maybe just disinterested in) either. The Book of Bunk, my 2011 novel about a Federal Writers’ Project that could/might have been, is about this. Every class I’ve ever taught has been an at least in part an attempt at haven-generation. A way of creating habitats for humanity.

This devastating song is an ode to that. Vietnamese-American Nashville native Julian Saporiti’s No-No Boy project grew out of his doctoral research, which sounds admirable, brave, and necessary, and which you can read about on his website.

None of that explains the magic in this straight-up folk-rock ballad.

Part of the pleasure, as usual, is in the instantly hummable tune; part’s in the beat that lopes and sways, those saxes that honk past like geese in formation on their way somewhere warmer. And yeah, a lot of it’s the words. The (true) story of a group of stellar Japanese swing band musicians corralled in an internment camp during WWII, the whole thing hums with forbidden delights traded in shadows (“Under machine guns, they danced beneath barbed wire”), with flashes of personality devastating in their person-ness (“Dropped by rehearsal in a tar paper barrack/Once he joined up, sister, it was on”). Ironies pile upon ironies; the band is so good that they get furloughed to play for “War bond drives in Powell, Mormons dancing in Lovell/A bunch of ‘Japs’ playing jazz at the Thermopolis prom.”

Certainly, there’s a sort of triumph here. But this song is an ode to joy recalled, not a celebration. The ferocity of the climactic “Locked up in prison camps for no fucking reason” may be on-the-nose, but it’s also essential. Yes, says this song, and these people, and this story, there are possibilities for joy in life. But chances are you’re going to have to make it. And then steal it.

I honestly don’t know why I don’t put this band on more. Every time I do, I remember how great they can be. They’re perceptive, they got more tuneful after Jason Isbell left, they play their dirgiest songs fast, they came up with a George Wallace track so steeped in nuance and insight that Robert Caro could use it as foundation for his next bio project. Maybe it’s the weight of strangling, paralyzing depression that Patterson Hood seems constantly to be hurtling out of or toward. Maybe it’s just that the Neil Young-meets-Skynyrd five-minute rockers they specialize in can’t help handling like muscle cars these days, and raise questions about why anyone still builds them.

Doesn’t mean they aren’t the apotheosis of the form, though. This cut is everything the Drive-bys do well; guitars that snarl without losing the melody, vocals that hook without losing the snarl. Some of the lyrics are a little obvious (“It’s a battle for the very soul/of the USA”), but how could they not be? Others are looming depression bomb-cyclones (“A world that ain’t worth knowing in the palm of our hands”). Title’s ironic, obviously. They hope.

Me, too, gents.

CARSIE BLANTON—Party at the End of the World

If all roads lead off the edge of everything, I’ll hitch a ride with the Truckers, but could you please drop me at Carsie Blanton’s house?

If there’s such a thing anymore as a healthy life path for an independent artist, Carsie Blanton’s living it. Honestly, she’s pretty much blazing it. Collecting news of good and productive things people do for each other and blasting that out in emails. Blogging passionately and honestly about everything you’d expect, and a few things you wouldn’t. Sticking to the pay-what-you-will/crowdfunding model of raising funds for her records and tours. And then—crucially—reeling off terrific songs that are sometimes about climate change or gender politics, but are sometimes just (or also) paeans to crushes in good jackets or sexy smiles.

This one’s all of the above. A salute to what we’re losing (or maybe have lost) as a call to action: “We can dance and we can kiss/Toast to all the things we miss/Snow in winter, rain in summer/bangin drums and banging drummers”. Really, it’s no more confident in our collective future than “The New OK”. But it’s happier about still having a present.

MONTPARNASSE MUSIQUE—Panter/Le Serpent

My choice to soundtrack the moment the party at Carsie’s house spills into the streets, through the neighborhoods, down the hills into the fraught and fractured cities. Algerian-French producer Nadjib Ben Bella and South African DJ Aero Manyelo’s project borrows from and skips through contemporary Johannesburg dance and club music genres, folds in contributions from some of the most recognized talents on the continent—in this case soaring vocals from the Congolese band Kasai Allstars’ Muambuyi on “Panter”, and Kinshasa’s Basokin on “Le Serpent”—to produce something that feels not only alive but steeped in life. In living things. There’s a rawness to those chattering guitars and these voices, which confront even as they sweep me away. But there’s also a sheen that comes from the beats, the hint of reverb and subtle production flourishes. Muambuyi hails from the Congo’s rainforest region, and the “Panter” lyrics, according to the project’s website, “call upon a tribal leader to reveal his mystic powers in front of his followers”. A risky proposal right this second, I’m thinking—see Eugene McDaniels entry below—but these tracks have power(s), for sure. They radiate collective spirit but also sound defiantly free. In the best pop music sense, they suggest what we can and just might still be for each other. And with each other.

EUGENE MCDANIELS—The Lord is Back

This came out the same year as Marvin Gaye’s “Mercy, Mercy Me”, which famously nestles one of pop music’s most apocalyptic warnings in one of its most velvety gloves. This song’s more a spiked fist. The groove sounds ferocious even now, that electric piano and guitar riff rumbling like a bike engine. It seethes and spits as McDaniels’s vocal grabs hold and puts it through its paces. “Panter” calls out for revelation; this is a declaration that it’s here (“The Lord is back.../The Lord is black/His mood in the rain.../He’s coming to make corrections”). Me—even as that groove rips me to my feet—I choose to take this as yet another reminder that we better get busy. Because if the Lord I’ve always heard about really does show up right now, and takes in what we’ve done...I’m thinking we might not like how She fixes it.

In a way, it makes sense—is perfect—that the song that best captures the claustrophobia of Covid isolation, Year Two for me—the epoch where anxiety about being shut in got married to anxiety about when to come out—was written in 2006, and probably would have stayed unheard by me if I hadn’t had the extra time trapped in the house to dig down to the bottom of a stack of discs that came out of a box I don’t remember packing from three or four moves ago. Innaway was from SoCal. This is from the first of two albums they made. It starts in a blur of strings which suddenly resolve—as though a hand got wiped across condensation on a window—into a jangling little acoustic guitar riff that sits atop an unsettled tambourine-and-hushed-or-brushed percussion shuffle like a splayed hand on a restless leg. “Using my tiny brain in my tiny room” goes the verse, repeated until it becomes mantra or maybe just hum. Unless he’s saying “Losing” instead of using, and eliding that first consonant. Works either way. There’s a surprising dropout near the end, revealing a buzzy electric bass groove, and then the vocals go all reverbed, and suddenly I’m back with my Bay Area gang again, remembering our first astonished listen through that riveting eponymous Voice Farm album no one heard (“Someone’s in the double garage...”), back when using/losing brains in those tiny rooms felt like adventure. Sounded like fun.

Alright, f that. Taking my tiny brain elsewhere. Woods of Finland, anyone? Not far enough? How about these woods of Finland, prowled by a pair of self-declared “akkas” (which their website defines to mean exactly what I expected it did) creating—their words—“string noise on the rotten roots of Finnish folk tradition”. I can’t speak with any authority to the rottenness, but I can say that something rich and toothsome and reassuringly wild has sprung from it. We start in shadows: a bit of woody percussion, whispering voices. Strings get plucked but dampened like caught breaths, The whispers get more forceful, catch and drop, coo and swoop. Halfway through—as it had to, as per its nature—the whole thing erupts into a dance no less bracing for being tuneful. It stomps, it saws, it swoons, it sounds like a world. Ours, even, with people still out there ringing it. For “Lastenkerääjä”, incidentally, Google Translate offers “children’s collector”. However you interpret that—look, I’m still several parts horror writer, and you can guess where my tiny brain went—I’m thinking it fits.

PLEASANT DREAMS—La Noche de San Juan

We’re up, we’re dancing. Time to make like the hapless protagonist of the only song by the Fall I’ve ever completely loved—and thanks forever for this one to my friend Scott—and go to Spain. This joyous shuffle pays homage to a popular Celtic festival marked by the lighting of bonfires to celebrate the summer solstice. Like Akkajee, Pleasant Dreams sound like their name here: sweet, gentle guitar chords lifted by a skip-stepping drum shuffle into a swirl of tune and tilt and arms-flung-wideness. Somehow, the clunky backing horn choir and the cacophony near the end only heighten that sense of welcome, as if the Dreams have reached out of the recording and handed everyone kazoos. And if that folk-derived melody has an inescapable ruefulness to it, a Station 11-style awareness of something clutched at as it passes...well, is that really so different than most of the melodies we remember and treasure? Or different at all?

THE PERFECT ENGLISH WEATHER—English Weather

Of course, to actually get to Finnish woods or a Spanish solstice, you’ll probably have to catch a flight, which will probably get cancelled, and the one you get shunted onto will be full of people wearing masks like fake beards and sizing up customer service agents to punch, and...maybe it’s better to ease back into each other? Take a nice walk?

All those decades I lived in the Los Angeles area, I would tell people I preferred the rain to the tyranny of sunshine. Now that I’m back in the Northwest, I’m relieved to find that that’s true, wasn’t a style thing. So here’s an ode to that, by a band who apparently loves rain even more than I do. P.E.W. are the acoustic side project of the family Pickles, Wendy and Simon, who as the Popguns had a jangle-pop/brokenhearted classic in the late ‘80s with “Waiting for the Winter”, but here sound whole and serene, stepping out into the “cool and gray”, to “hope it stays like this all day.” The words feel almost assembled as they go, sung as though from an exhausted parent to a not quite sleeping but no longer crying child, the guitar strumming stately though not exactly slow, the melody familiar at the second it forms.

While we’re strolling, swaying, feeling fine...how about a years-overdue check-in with a longtime fave? I can’t even remember how I found Finland’s 22-Pistepirkko thirty or so years ago now. At one point, I reviewed them for L.A. Weekly, tried to find partners to help bring them to the States to tour. Nothing came of that. I still regret it. It remains a dream of mine, to see them live one day. It’s still hard to define the magic they generate.

In their earlier, more garage-y youths, they careened like (possibly) unconscious post-modernists, dropping ripping surf guitar riffs atop “Blue Monday” dance grooves, throwing choruses where they shouldn’t, chanting lyrics that should have been nonsense (I mean, “Stuff is like we yeah!”??), except for the Buddy Holly-esque abandon and tunefulness with which they sang them.

They’re older now. Still making music, together and apart. Most of it’s slicker, these days. On the surface, anyway. But that magic’s still there. With its brooding organ and piano, its (again) not-quite-slow sway, “Borderline Blue”, from the ‘pirkko’s frontman, could almost pass for the Band, at times—except warmer—or great late Roxy Music (circa “Spin Me Round”). But that voice...a little too reedy, in just the right way...And that tune, a lullaby but for a grown-up...Framing more words I didn’t know went together...

I generally try to avoid critique-through-comparison. But listening to the 22s has always been like having a record-playing party with my craziest, listen-to-everything music friends. I’m so glad they’re still at it. And surer than ever that they know—have always known— exactly what they’re doing.

Feels good, this swaying, yeah? This slow dancing in each other’s vicinity, if not quite each other’s arms, yet? Let’s do that just a little longer.

Dean Wareham has remained a sly, consistent songwriter on his own or with any of his various ensembles for decades. But something really does happen to his guitar playing when paired with Sean Eden’s, atop the deceptively effortless rhythm section that drives this, his best band. “GTX 3” is from a 2017 instrumental EP called—perfectly, at least for my purposes, so thanks, Dean—A Place of Greater Safety. Whatever that glow is, it’s in the blending of tones as much as the notes. Beat couldn’t be more foursquare; the leads stay so tune-focused that they barely qualify as leads; the production amounts to a touch of reverb here, a winking organ backdrop there. But the cumulative effect...like looking out a train window at city lights passing. Or being one of those couples in that surprisingly gentle old Jonathan Richman song, “...not trying on the dance floor, no/They’re just moving slow...”

Leave it to Carsie Blanton to make a video for an anti-fascist anthem “featuring cheerleaders”, as she cheerfully proclaims on her Facebook post announcing the release. The song bounces and bops like most of her best stuff. It’s a fight song, and no mistake, but it delights in the fight; it not only could but must be played at that party she’s throwing at world’s end. But it also pulls no punches. Early on, when she chants “Thought we were rid of you back in ‘45”, you might assume Nazis, White Nationalists, all those (mostly) shared bogeymen. But by the end, after the rousing “So you want a white nation/(That ain’t the way we do it!)/Mass deportation (That ain’t the way we do it!”), she sings, “Put your money where your mealy little mouth is/And go right back to hell”, and it’s crystal clear that she’s brought the war all the way home.

EUGENE MCDANIELS—Supermarket Blues

Another terrific, skittering groove centered around twitchy electric piano, another set of lyrics that feel way too prescient or maybe just current fifty years after they were first released (to little notice). This is a story song of sorts: a Black man goes to the grocery store to return something, winds up getting harassed, then clubbed over the head, then an old lady calls him a Communist and wonders “how a savage like you/Know anything, Boy/You ain’t even white”, then the cops threaten him. Maybe the scariest thing about this song is that the world being described almost feels safer than the one we’re in now for this guy. For all of us. Near the end, the narrator wishes he’d “stayed home/And gotten high/’Stead of comin’ into this street/And havin’ this awful fight.” And then he sums up the zeitgeist—this one—as eloquently as anything else I’ve heard since March, 2020 (or maybe January, 2017, or the fall of 2008, or September, 2001, or...) with one single, exhausted, “GodDAMN.”

NO-NO BOY—Tell Hanoi I Love Her

A slow-strum, rueful little masterpiece about being a child of immigrants—meaning an American, and a Vietnamese-American, specifically—but also an ode to feeling young and lost and trying to make sense of warring identities that are really one identity, possibly even a shared one. The specific details—the “tiger mom” in the spangled t-shirt in the nail salon, the aunt who “cast a ballot for 45”—are dazzling, but the nuance and compassion that springs from this narrator’s confusion is inspiring. About that aunt, he acknowledges, “If I’d seen what she’s seen I might see her side”. He calls himself (or maybe all of us) “A fool to think this could ever be yours”, but follows that with “The in-between, that’s where we must explore”. The Hanoi this narrator loves is almost certainly one he’s invented or pieced together out of stories and memories that aren’t his and a young person’s dreams of kinder places. It doesn’t even sound like somewhere he’s been, and it certainly isn’t a revolutionary’s call to action. But the heartbreak in “Ain’t nothing sadder than some gook with an American dream” is real, and when he follows that with “Sometimes I think the most communist things”, well, how could he not? And my god, don’t you? Not because you really think that’s an answer. But because we’re still hoping to make something better, even if we’ve lost any idea of how. It’s exactly the kind of fleeting but stubborn hope I still see and treasure in my own kids, and in the kids I teach. To them, I say, keep hoping, y’all. Keep doing. Tell your Hanois (or Americas) you still dream we can make that I love you.

JACKSON EMMER—When the Lawn Gets Dark

A pretty song, for sure, and there is a compelling quality to the rasp in this Carbondale, Colorado artist’s prematurely trashed vocal cords, but really, this one’s effect on me probably comes down to that murmured, repeated question at its heart, plus the moment we’re in. We can scream (and I have); we can get active (and I try to, and have); we can doomscroll (but shouldn’t); we can run (haven’t yet, and don’t know where, but...). In the end, though, and for at least a little longer, I think I still believe that the only way out—meaning toward each other, or at least toward understanding and caring for each other—is by turning around and asking, “How did you get/the way that you are,” in exactly the way that Jackson Emmer sings it: gently, repeatedly, and like we want to hear the answer.

But you need more Jason Isbell himself.