A Bittersweet, Keening Goneness, Pt. 9: He Knew a Secret

A Top 10 List of My Father's Lists (#2 of 2)

Getting to the heart of this, now.

Below is the ninth installment in my ongoing series of posts about my relationship with my late father, Jerry Hirshberg, and our shared and separate relationships to art we loved and/or made. Each essay responds to a selection from my dad’s homemade card catalog, which documents his lifelong music collecting habit. I want each of these pieces to stand on its own, but this one really does pick up directly from where Pt. 8 left off, and ties up or refers back to several other themes in the series, so if you’re new to these, you might want to check out at least one or two of those, first.

This series will continue. I’m also thinking, though, of putting up some more exclusive new fiction shortly. Including maybe a little something special for October? Something, you know…seasonal? I sense that there are at least a few of you here who might enjoy that. I’ll see what I can do.

If you’re enjoying this work and would like to support it, please consider clicking the subscribe button. Don’t forget about my September New Subscriber Special, which is running until the end of the month.

He Knew a Secret: A Top Ten List of My Father’s Lists (Part 2)

Hmm. Not what I expected from music entitled “The Lost Art of Letter Writing”. At least not as a selection on a disc my father was making me. It’s not uninteresting. I like those violins gusting into and through each other. But it’s more Lost Art of Tearing Your Hair Out, yeah?

My dad had a go-to adjective for pieces like this: chewy. Which, to be clear, was descriptive, not evaluative. He was totally willing to labor through something difficult (see math, theoretical physics) if he sensed reward or revelation. But—to his eternal credit, as far as I’m concerned—he never mistook difficulty or complexity for intrinsic significance or quality.

Chew-as-needed. That’s our motto. I’m honestly not sure if he passed that to me or I did to him. It was certainly something we agreed about.

With no other evidence to go on, though, I’m betting that he, too, was disappointed or at least caught off guard by this piece. Maybe that’s why this Glendisc never got made. He started a compilation with “Lost Art...” as its center, realized it wouldn’t work, or wasn’t what he’d had in mind, and returned this card to the file.

In so doing, he revealed yet another purpose for his catalog: it’s a sketch book. Which makes so much sense. Why have I not thought of that before?

When I started this project, I wanted to grab and cradle everything I could that was my father. Frame but not shape it. Because he wasn’t just someone worth celebrating; he knew a secret, something about living well but kindly that so few other people I’ve ever met or heard of know.

He couldn’t quite communicate it, though. I think he thought maybe I could. Sometimes I think maybe I could. Except I don’t know it. Not all the way. Not like he did.

It’s in some of his paintings. Especially those sun-through-bamboo canvases from late in his life. Also in some of the designs. His half-finished sketches. These cards.

Where to next, Pops?

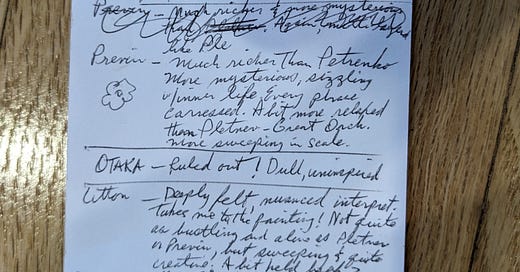

6. The Comparative Listening Lists

I am jealous of these. Understand them completely, but have no analog.

Well, one. Sort of. Late in my music-journalist days, maybe twenty-five years ago, I interviewed the seminal rock critic Paul Williams about his unending Bob Dylan project. Williams believed Dylan’s notoriously mercurial live performances, during which he never performs a song the same way twice and definitely never in the way audiences are familiar with and typically want, weren’t an act of defiance or apostasy but a quest for the perfect version of every single line or note, or at least the perfect version for any given night.

My dad wouldn’t have read Williams’s Bob Dylan: Performing Artist books. But he would have deeply respected the lunacy—sorry, commitment—of the enterprise. Williams dedicated most of the latter half of his listening life to studying tapes of every Dylan show from every tour, and cramming whole pages with analysis of the way “point of vieew”, say, from “Tangled Up in Blue”, gets delivered from performance to performance.

My dad’s “Comparative Listening” lists aren’t quite like that. The difference, I think, is that for each of his pantheon pieces—Mahler’s whole oeuvre, “The Rite of Spring”, Vaughan Williams’s “Sea Symphony”, and especially this one, by Rachmaninov—he had a Platonic Ideal in his head of what it should sound like.

What I love most about these cards is that none of the performances he collected was ever quite it. The Pletnev (presumably Russian pianist/composer Mikhail) version is close. It gets an underlined “Great”. The Otaka, though, is “ruled out!” With exclamation point! The Previn is “richer”, with “every phrase caressed”. Caressing apparently key to my dad’s Platonic “Isle”, because there’s more than one use of that word on this card. The Litton “takes me to the painting”, but is “A bit held back?” That goes for the Reiner, too, although that one’s also “Wonderful”.

More than anything else, this card reveals what my dad went to this piece for. It’s “mysterious”, full of “inner voices”, “reflective”, “sizzling with inner life” (although I do question the use of “sizzling” as descriptor here, Pop). He knew I love this piece, too. There’s almost no music I know that spirits me—and, obviously, him—so reliably to that misty, dark-skied someplace where breaths get scented and yearnings triggered.

Not satisfied, who cares about satisfied? Just triggered.

I could listen to the first two minutes of this piece once a day for the rest of my life. What I’m jealous of is that even on the days he didn’t put it on—which was most days, had to have been—my father apparently did.

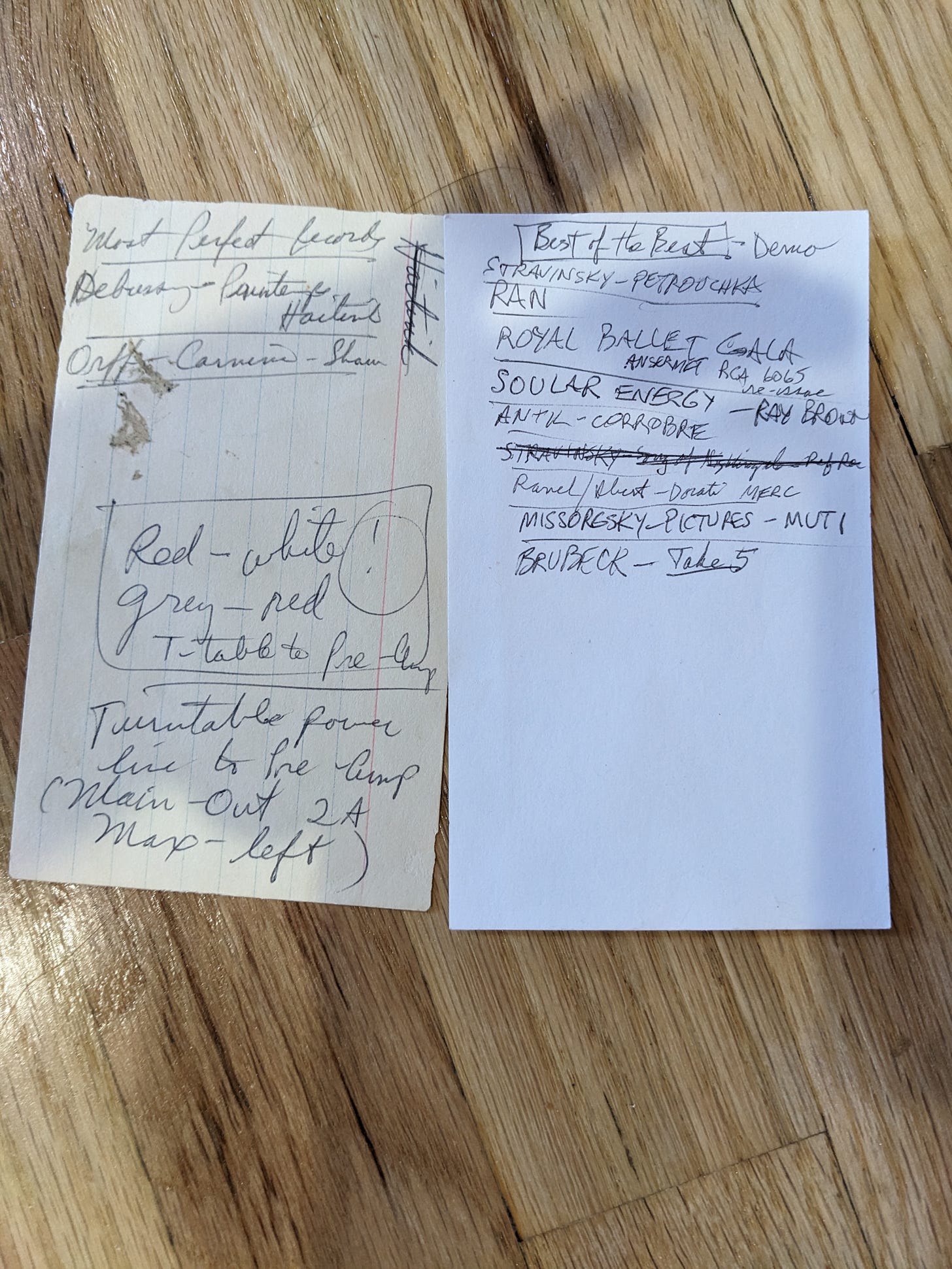

5. Top 100 All-Time Perfect Recordings

In his bathroom, for reading material, along with issues of ARTnews, and The New York Review of Books, and The Gas We Pass: The Story of Farts, my father kept copies of The Book of Lists. Multiple editions. To be used, and perused.

Sitting on the toilet, for him, was like settling into a library study carrel. Prime research time. Or just time he refused to waste. Like all time.

He also provided copies of all of the above in the guest bathrooms. Because he assumed everyone would want to use minutes properly. And because he hoped guests would emerge with all-new ideas worth arguing about. Enthusing over.

But as in so many things, my dad was a list-making pro. Meaning that unlike his sets of music to play specific friends, or his Forgotten Treasures compilations (see below), and definitely unlike his shopping lists, Best of or Greatest Ever compendiums were a game. To be played, never finished. Taken seriously only in the moment of their generation. Worth generating purely for the purpose of provoking chatter, or better still, (re)discovery.

Hence the cross-outs on every single card of this nature. And the fact that he also used the only card I’ve found labeled “Most Perfect Records” as a scratch-pad, with what looks like some sort of Enigma color-code encryption that has nothing to do with perfect records plopped in the middle.

Which brings us to our bonus quiz, for frequent readers of these essays: can you crack the code in that box? Do you know what those colors signify?

I’ll put the answer after Great New Ones below.

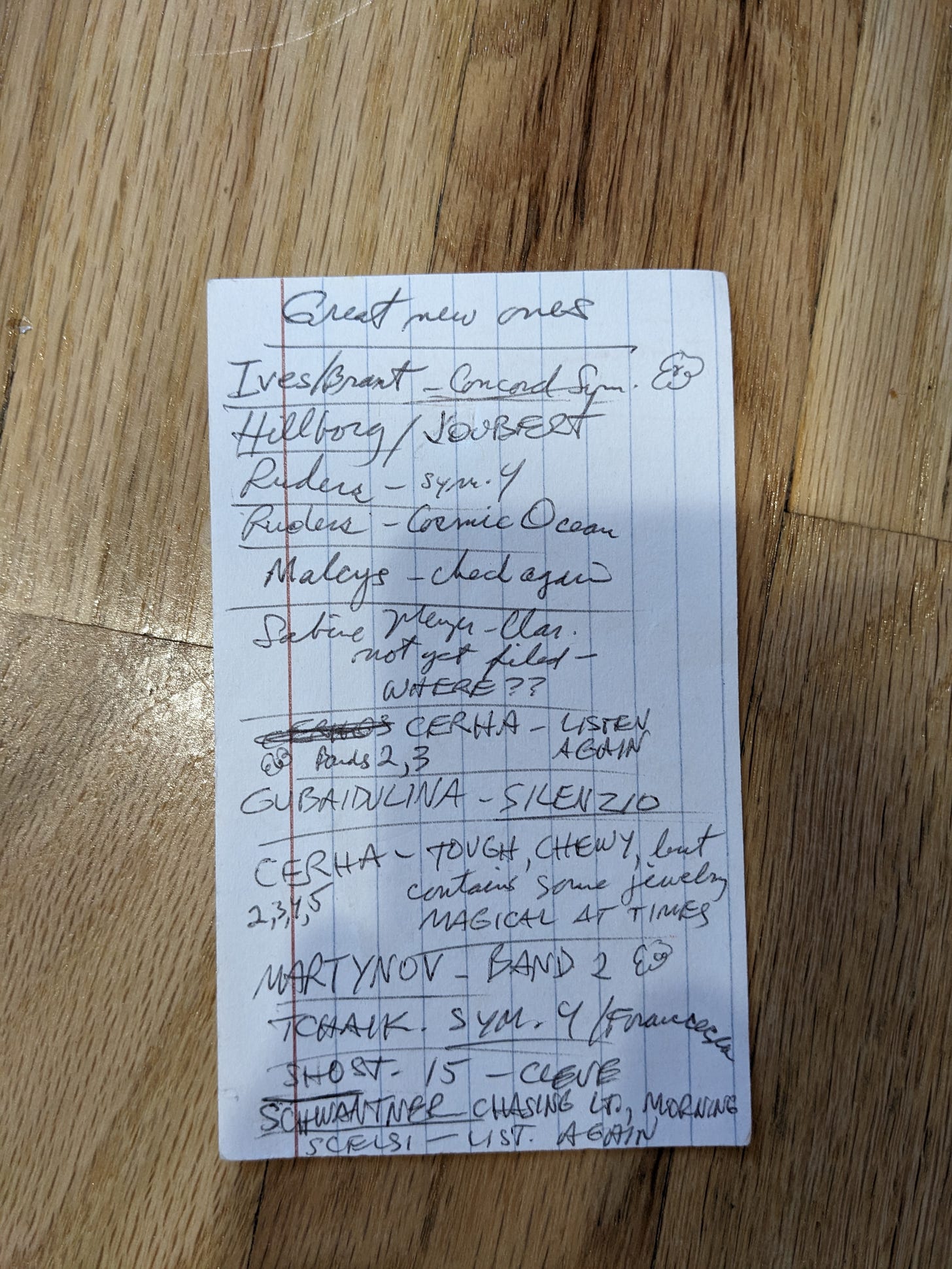

4. Great New Ones

Once again, I only almost understand these.

My dad rarely bought in bulk. As noted elsewhere, even late in his life, when he was more than comfortable, he spent judiciously. He loved finding a title he was hunting, but loved finding it used even more. Not because he was cheap—he would have had to care more about money itself—but because budgeting added to his pleasure. It forced choices. Sharpened his discernment. Deepened that treasure-hunt sensation, which was always what he loved most about record shopping. Me, too.

Because of that, though, he only had so many recent purchases at any one time. So why did he need a list? When did a recording drop out of the “Great New” category and just become Great? Maybe he had already filed these CDs on his shelves, but wanted to keep them in frequent rotation?

I also point out the entries with descriptions (note “CHEWY” beside the Cerha disc; told you he liked that word). Are those rough drafts? Proposed versions of official catalog entries he was in the process of passing out of committee, submitting to the full Jerry House for final notecard certification?

Then there are the directives to himself. Most often, “Listen again” or variation of same. I do get what he’s up to, there. Those are discs he loved less than he expected at first listen, but still hoped he might someday.

By far my favorite note on these cards, though, is, “not get filed—WHERE??” Referring, I’m pretty sure, to a disc he knew he’d bought, remembered hearing, and lost track of somehow.

Which makes me laugh (although he wasn’t laughing when he wrote that; no way). Honestly, to me, that may be the funniest single phrase in the entire card catalog. And the sweetest. The Jerry Hirshberg equivalent of “WHERE ARE MY KEYS?!”.

It’s the least distinctively my-dad, and the most human. I’m betting that before (and possibly after, and more than once) scrawling that line, he barked at my mom, or anyone else who happened by, asking where they’d put the missing disc. As if anyone would have dared. Or bothered.

Because he really was a piece of work. Finicky, tetchy, irrational sometimes. Very much a person.

Which just makes all the other things he was—joy seeker, joy bringer, art inhaler, art producer, people-loving hermit, talent nurturer, life cherisher, lover of games of all kinds who couldn’t be bothered to remember even the rules he’d made up; goddamn, there’s so much I haven’t even touched on, yet—that much more amazing to me.

BONUS QUIZ ANSWER: They’re instructions, of course. For the order of turning knobs on the then-current pre-amp and amp to wake up the Misters.

EXTRA CREDIT BONUS QUESTION: Have you worked out for whom those instructions are meant?

They’re for himself. He must recently have changed or added something to the system.

He had other cards for my mom, his kids, house guests. Those had only instructions on them, and stayed glued to the inside of his cabinet, and came with IKEA-style sketches in case you were illiterate. They were also much more carefully spelled out. To the point that—in his imagining—the dog could have turned on his stereo.

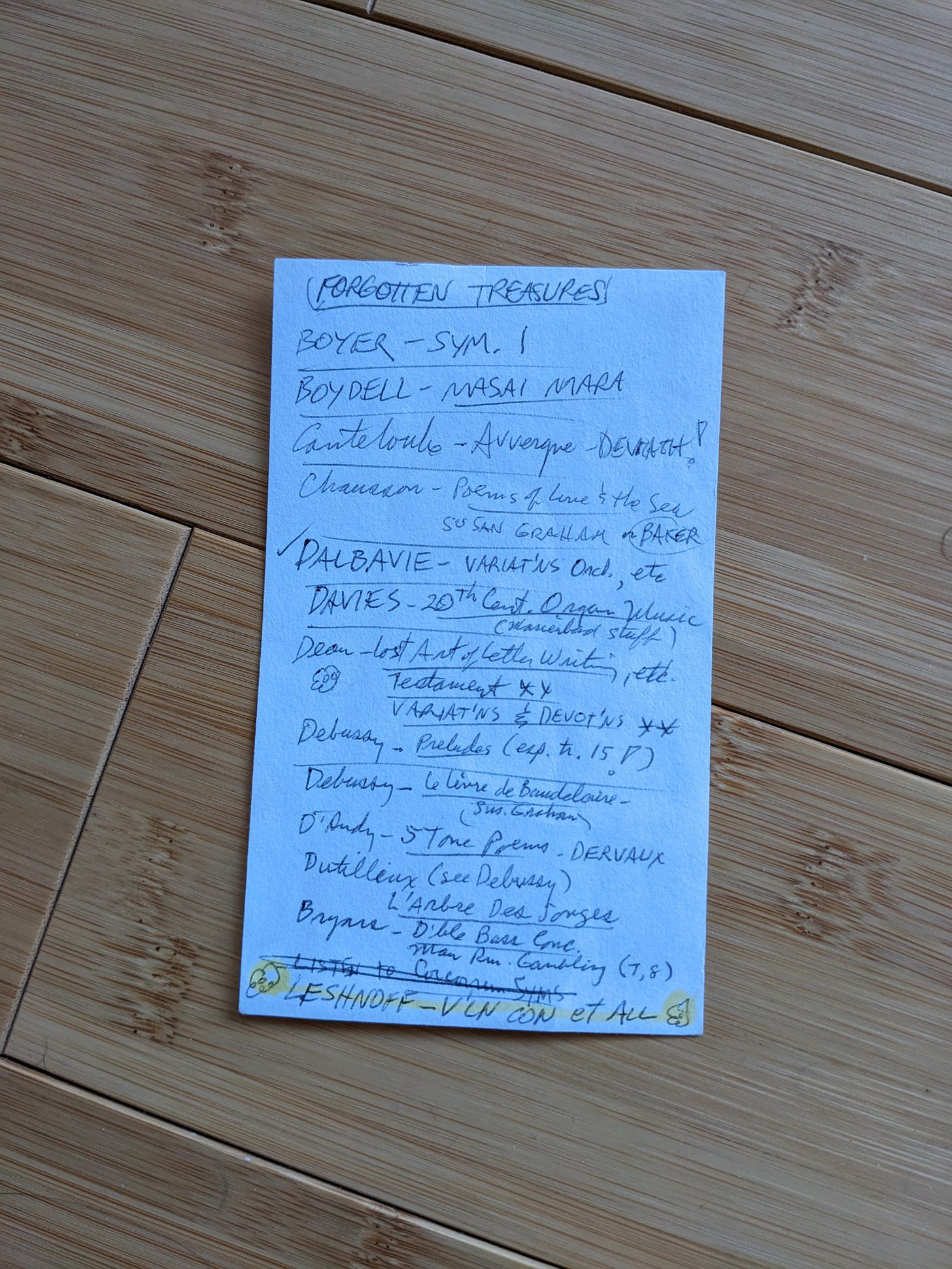

3. Forgotten Treasures

My only question here is when this got made. After all, the discs on it clearly weren’t forgotten anymore, because here they are. But did he have to listen to them again before bestowing “treasure” status?

I’m betting no. I have a theory on this one: it’s a to-do. A go-back-to-these. And it ranks this high on my list of my father’s lists because I can so, so imagine the nights he spent making it. The delight those nights must have brought him.

Mostly, when he wrote these particular cards, he was alone. Or, sure, with my mom or his kids in the room, but busy with their own things. He had a Great New One on the stereo, and his speakers up and humming

And while he listened, he went to his shelves, probably only one shelf at a time. Pulled out every single disc there, and held it in his hands. Remembered where he’d gotten it, and who was with him. Sank into a memory of wherever he’d been when he’d heard it last. Or the effect it had had on him.

And then returned to the couch, and added the music that reverberated most (and best) to this card.

With exclamation points. Asterisks. Stars.

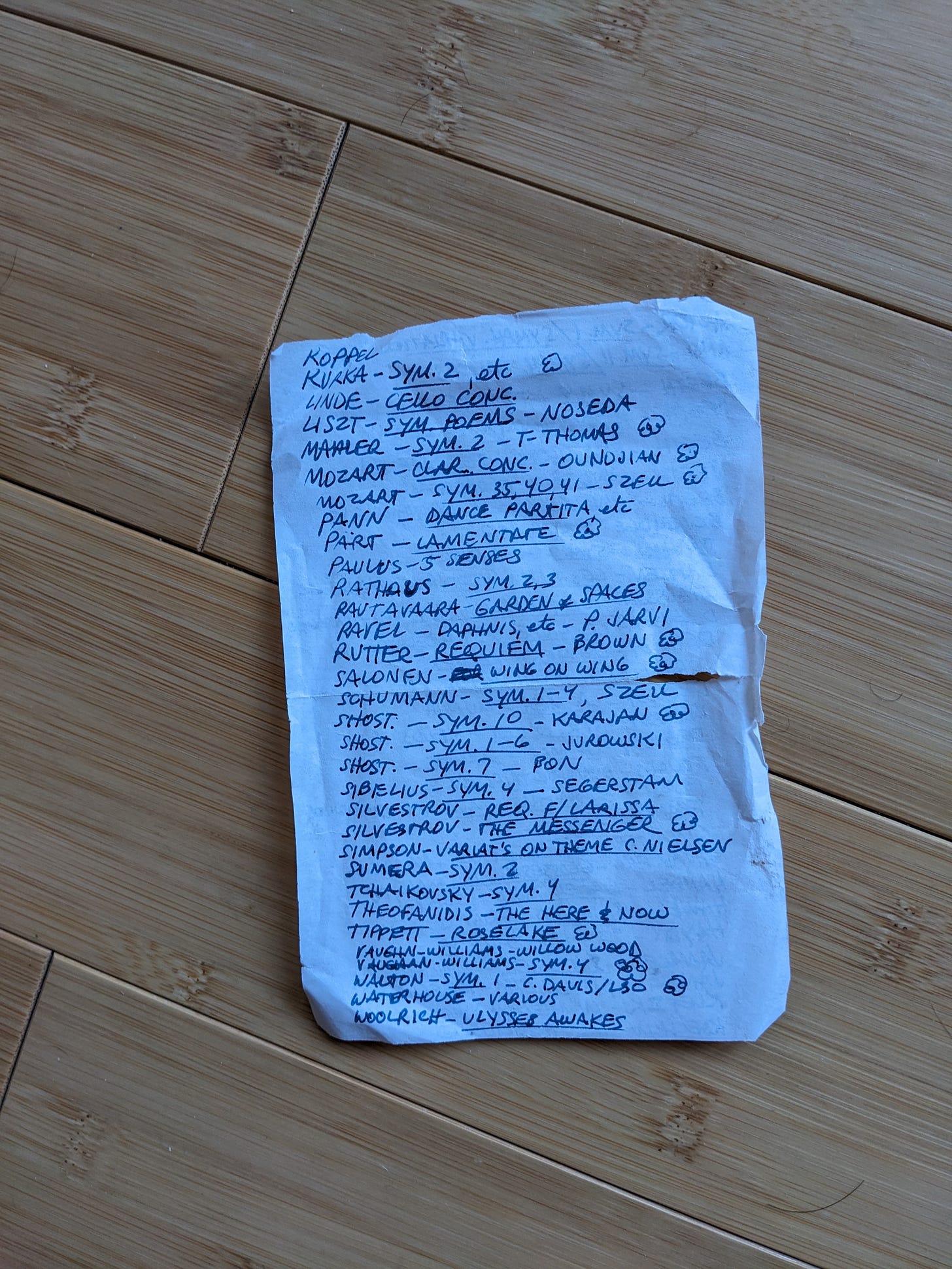

2. Shopping Lists

Just lists, these. Found in his wallet, his night table drawer, the glove box of his car, the pockets of his hoodies, next to his computer, beside the floss above his bathroom sink. With rare exceptions— there’s a Supreme Records to Find card, for example— they’re not even categorized or dated. And even that card, I suspect, was haphazardly updated, or a one-off, prepped on the eve of a trip to Amsterdam, or Japan. Or up to L.A. for a few stolen hours at Amoeba with me.

No descriptions. The random usage of capital letters really was random in this case. No exclamation points. Those were for moments of finding. To punctuate the yipping.

So why are these almost my favorites of all my father’s lists?

From the moment my father realized there were things in life worth hearing, seeing, knowing, chasing—so, from right around the day he was born—he chased them. He did that by talking to people. By reading. By driving hundreds of miles on a free Saturday to scout a new possible shop he’d heard about. By mastering just enough internet to play Scrabble with my aunt or me and strike up 84 Charing Cross-style relationships with clerks in classical specialty stores in Germany or the Czech Republic. By devoting countless hours and evenings—possibly the most fully engaged of his fully engaged life— to researching in reference guides, magazines, on websites.

Shopping, for him, was not an act of consumerism, but optimism. An expression of unshakable certainty that there were things out there even more wondrous than the wonders he already knew about. That there were people sharing the planet with him who were capable of creating such things. That the next day alive really could taste as good and magical as the days he’d already lived, and loved. That it probably would.

My dad lived like that until the instant of his diagnosis with glioblastoma (after which he commenced shutting himself down with a totality and speed that startled us all, and that I don’t want to write about here; that’s what my short story, “Over”, concerns, if that’s what you’re in the mood for).

In other words, whether by instinct or will or both, my dad figured out what made living good for him. And then lived like that.

Seems so simple.

But if so…

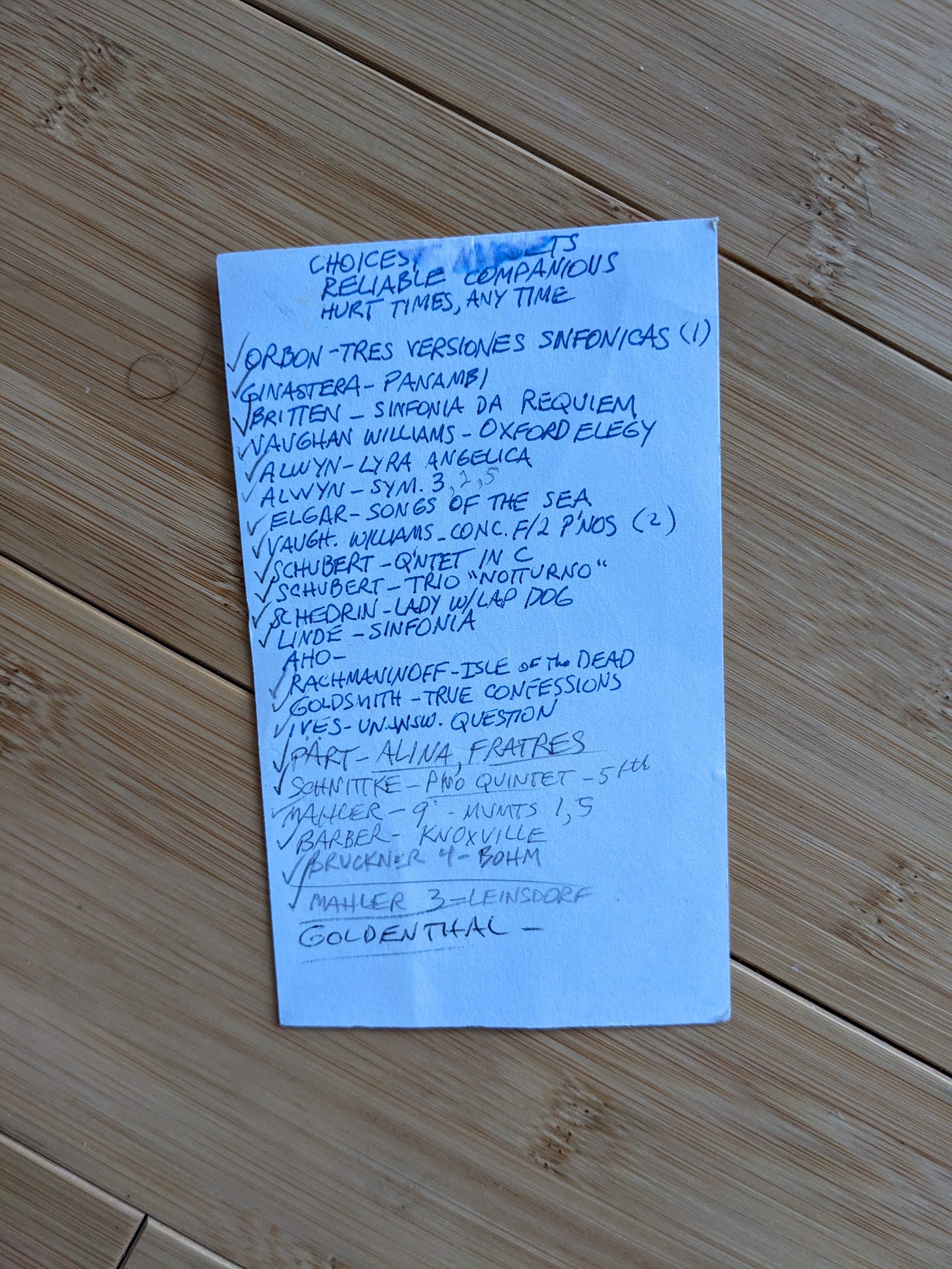

1. Choicest Reliable Companions. Hurt Times, Any Time

I mean, of course this is my favorite. It’s the most telling. My dad, all the way down. Just reading these titles is like breathing his air.

But...even if you’ve never heard any of this music...look at the words: “Requiem”; “Elegy”; “Notturno”; “Unanswered”; “Question”; “Dead”.

Long before my dad got sick, way back in the rest of his life, in his not dying/alternate plans days (see pt.3 ), I heard Laurie Anderson’s “World Without End” for the first time, and it sent a shudder through me that I’m not sure has ever passed completely. It seemed to capture so much of the experience of having a father. Of having my father. Of having had him. Even while I still did.

“When my father died

We put him the ground

When my father died

It was like a whole library just burned down.”

Except that my father left his library. And his card catalog, to guide anyone who cares to visit. When he was living, the catalog and collection really were one of his organs. A second beating heart. Maybe just his heart.

Now it’s his archive. It still echoes with him. The echoes don’t fade, as long as I sound them. But they’re no longer him.

I say of course this list is my favorite, but now, as I type, I’m not even sure that’s true. Maybe this is simply the card I most immediately recognize, and fully understand.

You loved Dvorak’s Slavonic Dances as much as anything here, Dad. Played it more. I know you did. But when you went to chart your “most reliable companions”, you listed the pieces that hurt you most. Haunted you most.

It’s a gift you gave me, I guess: that longing for (or trust in, even joy in) melancholy. In plumbing the well of the hurt we’re capable of feeling. Or can’t help feeling, underneath all the other marvelous things we can feel.

It’s where your paintings came from. Even the happy ones. It’s where my ghost stories come from. Possibly all my stories. Even the ones about you, which may be the happiest I have to tell.

Of all the gifts you gave me, this is the one I most wish you’d take back.

Please, Dad. Take this one back?

No—wait.

Don’t.