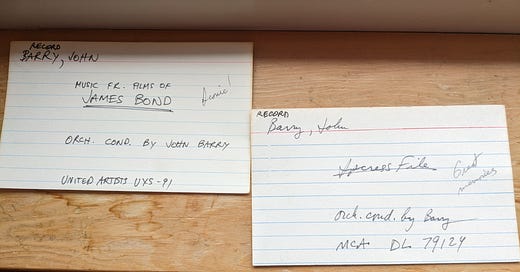

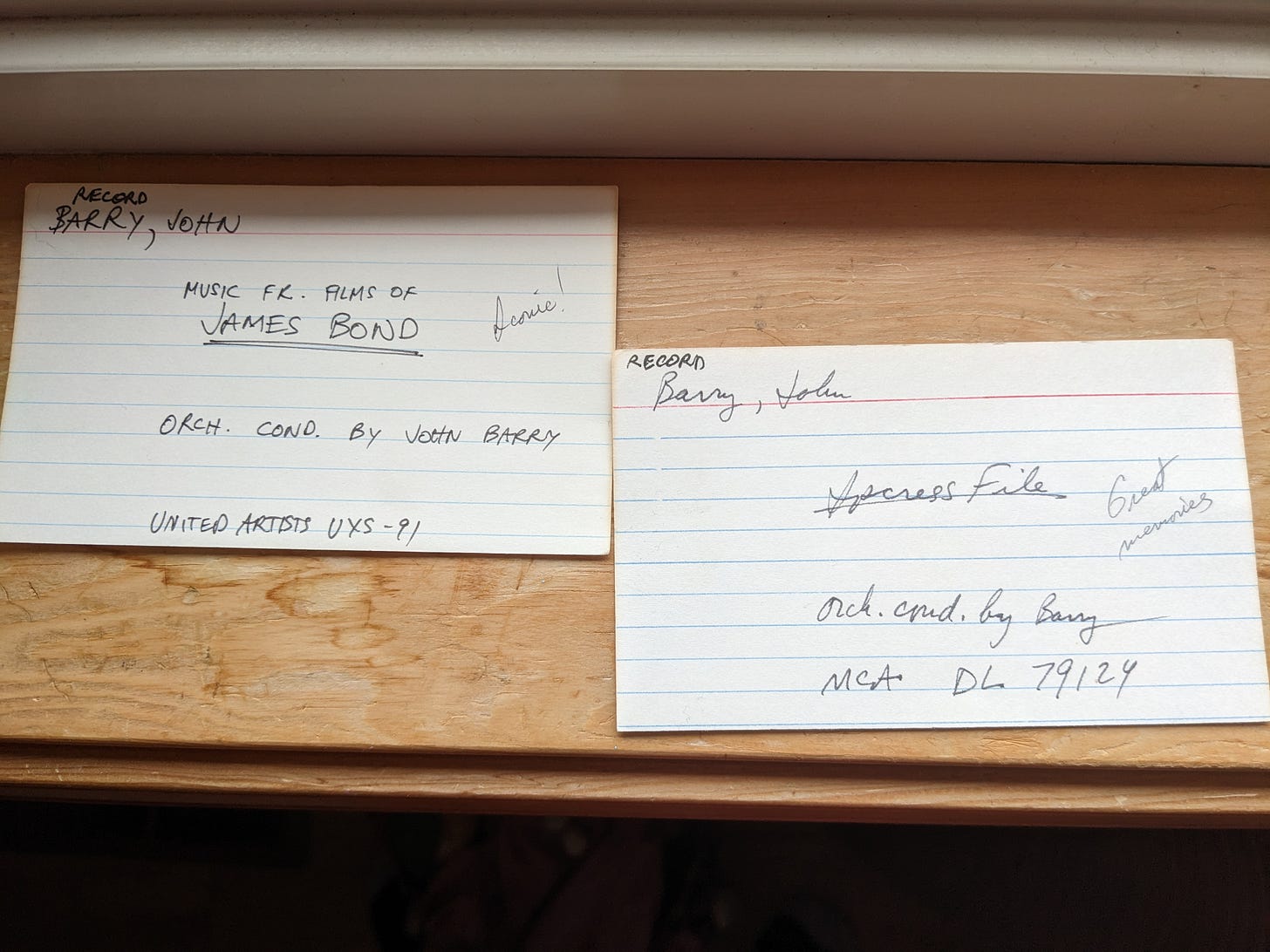

(Note: This is the third in an ongoing series of essays exploring my relationship to my late father, and art we both love(d), and our ways of sharing it and living through it. Each essay responds to a selection from my dad’s homemade card catalog, which documents his lifelong music collecting habit. I certainly mean for each of these pieces to stand on its own, but suspect their effect will be cumulative. If you’re new to the series, you might want to start with Pt. 1.)

Dadfinger

All right, art snob. Let’s settle this once and for all:

In a way, it’s good to know you really were snob all the way down, Pops. In your record and cd collection are dozens of rock and folk and jazz and soul albums. You didn’t make a single notecard for any of them.

Yes, I remember driving in cars with you. Waiting for Jim Svejda (you loved him), your deejay of choice on classical public radio, to get on with it, play the next canonical composition, so I could watch you clench. Scrunch the face. And then—usually by the end of the first extended phrase, often at the first chord, just from the texture of the strings or the ambience in the recording—name not just the piece but the orchestra, soloist, conductor.

I know you really did have all that music in your head. I know you loved it dearly.

I also know you. Knew you. And I am positive that at least half the time, maybe most of the time, what you were walking around humming when you were with your kids, or anyone’s kids, or maybe anyone, period, was “ma-ma-ma-ma-ma-ma-ma—ma-ma-MAMAMA”. Just to keep yourself primed and ready. So you could whirl and burst, at every opportune moment, into “Surfing Bird”. Or doo-wop bassline Duum...da-dums. Or full-blown Buddy Holly yips.

My dad didn’t just love that music; he made it. Yeah, yeah, he was a phenomenal clarinetist, more on that some other post. But the only music he ever got paid to make was the (irritatingly good—how is it possible you were that good at that many things, Dad?) regional hit singles he penned and then performed with my uncle Bert and their band, as Jerry Paul (that’s him) and the Plebes, having taught themselves two chords and started jamming just because they loved the feel. The best was called “Sparkling Blue”. It still sounds great.

Decades later, he and I watched the first episode of that disappointing PBS series about the history of rock music, which highlighted the ways early rock-and-roll terrified parents and authority figures with its challenges to racial divisions and unleashed youthful anger and sexual energy And my dad—wrongly, or just narrowly, viewing it all through that kind, perceptive, but oddly naive lens of his—shook his head. “That’s not true,” he told me. “It was just the happiest sound we’d ever heard.”

So, yes, classical. And yes, rock and soul and jazz and pop.

But the music my father had running most often in his head almost certainly came from film scores.

Especially that one. Cue guitar:

Dung-de-de-dung-dung, deh-deh-deh, Dung-de-de-dung-dung...

At least he deemed the scores worthy of cards. Though the cavalier platitudes he scrawled on them hardly do justice to their importance in his world. I can’t claim to know the plot of the movie my father dreamed he was living. I’m not sure he knew it, either. Plot was not his primary concern. There was no arc, no three-act structure. It may have been more than one movie.

What I do know is that it was all-consuming, comprised every moment of his life. And he definitely knew his role in it:

Spy. Fun Spy, from the hopelessly besieged Nation of Fun, trapped forever on the wrong side of Checkpoint Charlie, behind enemy lines (meaning on this planet, among so many gray, funless beings), in perpetual danger of being found out.

His mission, which he didn’t so much choose to accept as invent?

Never get got. Which meant that “take the kids swimming” became hours-long games of Underwater Knife Fight (a la Thunderball), the most important moment of which was the en garde, involving ritual locking of eyes while hovering below the surface, and then simultaneous unsheathing of finger-blades from between our teeth. The extended and operatic death enactments at the end of each bout were also essential. Synagogues were for sneaking out of, especially on Yom Kippur, particularly if there was a Burger King across the street. Time was for stealing. Days simply vehicles for experiencing more music.

And work?

When I was maybe five, my father brought home a copy of a Super 8 film smuggled out of his design studio at General Motors. In our house, it was called “Daddy Goes Bananas”. Mostly, it consists of my father and seven or eight more of the most talented automotive designers in the country at that time careening (J)erry-rigged, foot-propelled go carts around corners, down gray, institutional corridors, through gauntlets of flung modeling-clay bombs.

I used to think that movie had other names in other houses. Or that all the kids assumed, as my brother and I did, that “Daddy” meant their daddy.

I’m not so sure, now.

Years later, not long after Nissan hired my father to run its first North American design studio, they sent a formal board delegation from Japan to meet and get a sense of him. He took the group to a restaurant right on the beach in San Diego, and apparently managed to blend in with the rest of the grown ups all the way to dessert. Then, abruptly shoving back his chair, he told them, “Watch this”—only a couple of these people spoke English, and I have no idea how what follows was translated to them—grabbed the bread basket, and leapt to his feet.

Seconds later, he was out on the sand, in full view of the entire restaurant, waving a bread crust in the air. I wasn’t there, but the way I heard it, he maintained that pose—like the Statue of Liberty, except hopping up and down and making seagull-summoning sounds—for a good five minutes. Long enough for serious sanity concerns to ripple through the Japanese.

And then—like Suzanne Pleshette in The Birds, only happier about it—he vanished in a cloud of wings.

There’s another movie of my dad at work. A legendary one, and not just in our house. It doesn’t have a name, as far as I know, and doesn’t need one. It’s a documentary. Actually just a document, of a historic moment. The inevitable culmination of—and, in certain ways, revenge for— years of pop-up homemade squirt gun fights, lunchtime (or work time, whenever) paper boat battles in the fountain out front of the Nissan Design building, practical jokes my dad perpetrated. Everyone I know who has seen it or helped make it just calls it the earthquake movie.

It is devoted, in its entirety, to the moment pretty much everyone employed at Nissan Design—so, understand, modeling masters, expert engineers, pedigreed applied arts geniuses, to all of whom my dad had given years and years of license and encouragement—rigged the studios and staged an earthquake. Lucasfilm Light and Magic couldn’t have done it better. Walls shake, and framed photographs leap from them. Papers and charcoal pencils hurtle from drawing tables. Light fixtures tilt and sway. The actors—perpetrators—adopt the barest gestural expressions of alarm.

All in the service of getting my dad to do exactly what he does. Which is glance up, look wildly around, throw his arms out to either side (you know, to maintain balance). And then finally, fatally, in a moment that has to have surpassed the creators’ wildest dreams, yell, “Did you feel that?!”

So many people have copies of that clip. Love to play it. Loved to play it for my dad. Laugh at his gullibility. Which is hilarious. And beside the point.

The thing is, what that clip makes abundantly clear is not just his gullibility. Also, my father didn’t crave damage, never wanted anyone hurt.

But make no mistake; he wanted the earthquake. It was good for his movie.

Right before he quit automotive design, my father wrote a book about his management philosophy called The Creative Priority. There are creativity theorists who rate it as an exceptionally insightful treatise on fostering authentic inspiration in business environments. It might well be that. I think it is. It might also be a spectacularly sustained and eloquent excuse for acts like closing the entirety of NDI on a Friday afternoon and taking everyone to the first matinee of Silence of the Lambs. Which he did, either because his team was stuck on a current project and needed its artistic gears greased and reset, or because he really, really wanted to see Silence of the Lambs.

It might be a manifesto. It’s probably all of these things.

My father didn’t devalue work. Far from it. He just never distinguished any work he did value from play. He spent the first couple years of his “retirement” furiously honing his clarinet chops back into shape. Which of course he managed to do, so successfully that he wound up giving concerts and recording a CD with a flautist from the San Diego Symphony. Then he returned to the work—play—he’d always loved most: painting.

Returned, as in eight-to-ten hour days, six or seven days a week. For years. Because it was fun. The prestigious New York gallery show his canvases eventually landed was not beside the point—my father did hunger for accolades, they were part of his fun—but it wasn’t the point.

Reading through the notecards, I remain mystified at how he balanced all that joy he sought and treasured with his lifelong adoration for music and films designed to crush. Trigger melancholy. Lure him to rainy windows through which he could stare while quietly weeping.

I also don’t know why that feels so mysterious to me. It shouldn’t. I inherited both loves from him: of fun, and of quietly weeping at windows.

But I think his duality was different. More...dual. His pursuits of joy, and of melancholy, were distinct pieces of the puzzle that was him. In me, they’ve run together into a more nebulous clump.

Like any decent horror writer (or maybe writer, period), I can pinpoint the exact moment when I realized I was going to die someday. I was six years old. I was walking past a mirror. Suddenly, I found myself staring into the glass, into my own eyes. And what I thought—and couldn’t stop repeating, over and over, to myself— was, You will stop.

I’m not sure I’ve ever fully disengaged from that moment. It still reverberates so vividly.

I also remember asking my dad about it. And his response. Which was a nod. Which wasn’t satisfying or helpful. So I asked him if he was going to die. Even though I already knew the answer.

He stood there a second. Then he shrugged. “I’m not dying,” he said. “I have alternate plans.”

Dung-de-de-dung-dung, deh-deh-deh...

Gorgeous! So many layers to his being you’ve captured. Some known most not. Thanks for sharing him and you Glen. I can still see that devilish look in his sparkling eyes. Wonderful memories

Well, you do have a way of landing the punches, my friend. Beautiful work.