Below is the fifth installment in my summer-long series of posts about my relationship with my late father, and the art and experiences we both loved. After this piece, there will be a break from these for a bit.

Next up here will be my quarterly music round-up, plus some fun and evolving news.

I am already working on more of these essays. They clearly want and are going to be a book. Which means I need to save some of them for that.

Of course, the more support I get here, the more I can justify putting work up for all to read. So, if you’re enjoying this Substack, and you’re able and so inclined…

Or, if you don’t want or can’t do the commitment, you could buy me a cup of coffee. Either way, I’d be honored. And grateful.

If you haven’t read the earlier installments in this series, here’s a quick user’s guide:

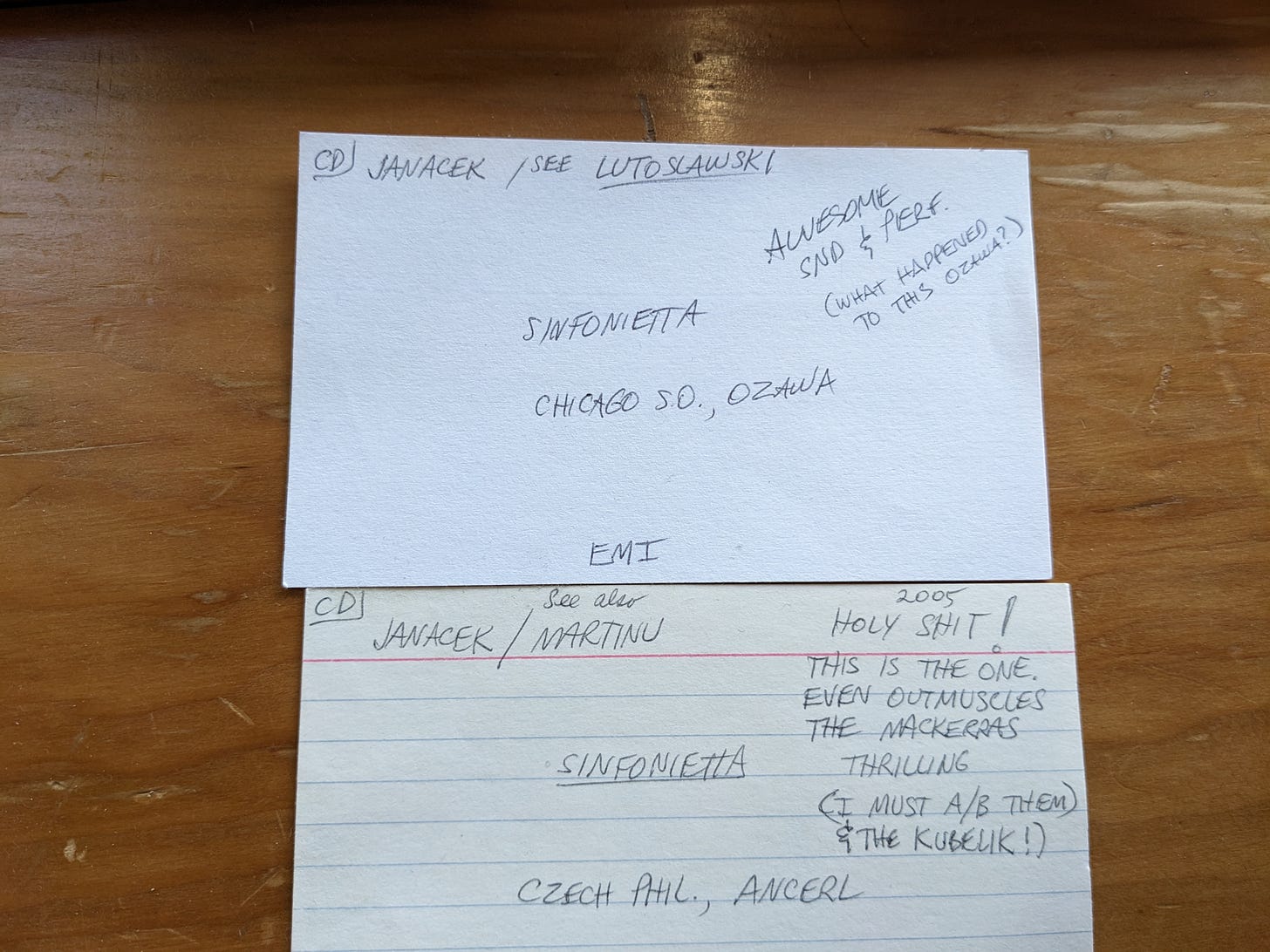

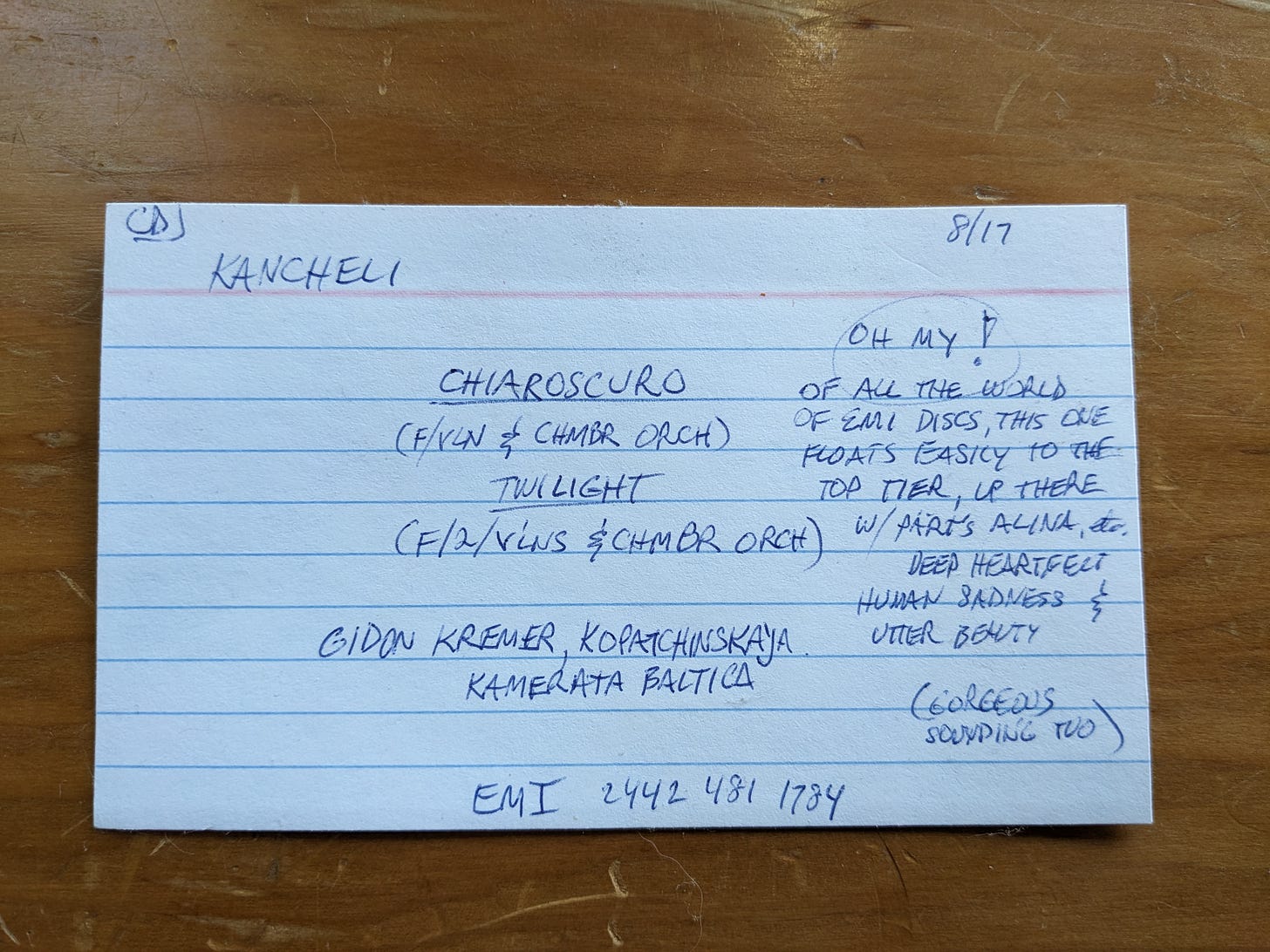

Each piece in this set responds to a selection from my dad’s homemade card catalog, which documented his lifelong music collecting habit. I certainly mean for each essay to stand on its own, but suspect the effect will be cumulative. If you’re new to the project, you might want to start with Pt. 1 and then make your way through the progression.

Is This Brain?

I’ve already told you already about my dad’s internal movie. Movies. His starring roles. There was the rock-and-roll upstart pic. The spy thriller. The disaster flick. The Bergman-esque philosophical exegesis. The sweet, soul-crushing weepie. The rebel comedy. (For more on those, see the Dadfinger post from a few weeks ago.)

At least one of those narratives was running in my father’s head every second of his conscious life. Given the joy with which he lived—the way he chased and cradled and created it—it’s surprising how susceptible he was to nightmares. He rarely said what they were about. I’m not sure he wanted to know. Maybe, simply by his nature, he flipped the opening of Shirley Jackson’s Haunting of Hill House on its head. Even he, with all his creative force, could not “exist sanely” under conditions of absolute not-quite-reality, or willed reality; even Jerry Hirshbergs are condemned, sometimes, to confront raw, lived experience. Even if they do it in their sleep.

Crucially, though, it wasn’t just his own life that he converted to cinematic gold. Every person with whom he interacted was a new and potentially riveting character to study (and help create, and infect with delight). Every new play of shadow and light a possible painting. Every new event a development.

And every new record or CD purchase could trigger or just be all of the above.

As noted elsewhere in these essays, my father’s notecards sometimes are directed toward specific people he knew (his friend/fellow designer/record shopping partner Lenny, my brother Eric, my mother, his brothers-in-law Jeff and Henry, me) or didn’t know (the critics at Gramophone and Fanfare, classical radio commentator Jim Svejda, the composers or performers themselves). At other times, they turn inward, constitute individual episodes of his never-ending private dialogue.

But now, reading the cards as a set, I see that mostly they’re talking to each other. My father didn’t just curate or catalog his collection; he watched it, for days and decades on end, like a little kid mesmerized by an ant farm. Or himself watching a movie.

Movies.

Who will win? What will happen? Who has reached the classical music summit? Who has resurrected or lost themselves?

Whether or not a new recording disappointed, it was guaranteed, at the very least, to become a thrilling new episode in its own epic series. Hence, as in the cards pictured above, one disc “even outmuscles the Mackeras”. Another “blows away the new Miller”. A third causes rueful wonder: “What happened to this Ozawa?”

My dad read and enjoyed arts criticism, but I I rarely heard him apply it to his own listening/viewing. He would have known what auteur theory was. But its only direct use in his life was as cataloging tool, for the purposes of telling—creating—narratives. Crediting a conductor such as Seiji Ozawa, for example, for an exhilarating new recording played into a long-developing plot line he was following and/or concocting. (In this case, firebrand champion of challenging 20th century composers rockets to stardom, fights for young talents, then takes up directing the Boston Symphony Orchestra and phones in “Ode to Joy” performances for years...until suddenly “this Ozawa” surfaces once more and assumes his rightful place on one of my dad’s collection pedestals.)

One secret to my father’s happiness was his ability to forget that the stories he told himself were at least partly ones he had imposed. Or proposed. Pitched, almost, to the clueless and soulless producers in charge of the universe. By the time he’d developed his plots, he already believed them. They were simply happening.

He lived that way, too. Experiences as unfolding arcs, with beginnings, middles, twist endings.

Take, for example, Ohio State football. Yet another complicated joy he gave me.

There’s a lifelong taunt aimed at me from certain quarters of my family about why I am an Ohio State fan. I grew up in Detroit, after all. I was brought to sports not by my father but my uncle Jeff, a Michigan Man to his very bones. He was in college and law school there when I was young, and came to our house often, and took us to games. My brother, understandably, sided with my uncle, and with our neighborhood friends, right from the start.

Why didn’t I?

Honestly, I’ve never understood that question. I’m a Buckeye out of loyalty to my dad. And also, in a way, to Jeff, who I loved dearly, and who died stupid-young of pancreatic cancer, and aspired to the title of World’s Most Competitive Man. Certainly, he had no peers as World’s Most Aggravating and Committed Opponent. Precisely because of that, it was more fun for him— and me—to have a bantering partner.

Also, I think I enjoyed being the villain sometimes. Or maybe just different. It was good for my movie.

The question my family really should have asked is why my dad was an Ohio State fan. Okay, he grew up in Cleveland, and he did attend OSU. But only for two years, before transferring to the Cleveland Institute of Art for all of the educational experiences that mattered most to him, and then moving to Detroit for almost two decades. If he ever so much as went to a game during his time in Columbus, he never mentioned it.

And while he came to cherish watching the Buckeyes on Saturdays later in life—primarily so he and I could call each other constantly during the games—the only football he really loved was the backyard kind, with outlandish trick plays: the hidden ball stuffed up a shirt; the kid flung in the air to catch a pass over the World’s Most Competitive Man’s outstretched arms and outraged objections.

I sometimes wonder if he rooted for Ohio State because Jeff wanted him in that role. How could Jeff not? With what other person, after all, could he (or anyone) have generated, and lived, the bowling story?

Let’s call this The Father Who Flew by Himself. My family’s very own Just So story.

This was 2002. I think. It might have been 2000. Somewhere in that run of years during which Jeff, whose titles also included World’s Most Skilled Finagler of Impossible Tickets, kept coming up with ways to get us into the Ohio State-Michigan game, and so groups of us met in Ann Arbor or Columbus. Sometimes it was just Jeff and his friend Marc (another Buckeye fan who didn’t go to Ohio State) and my dad and me. Sometimes my brother was there, and my uncle’s kids, and some cousins. The best parts of those weekends were the Friday nights: the meeting up, the banter, the local pizza, and of course that year’s designated Family Compete. Which, some years, was touch football on the quad. Some years air hockey. Once, it was dropping a tennis ball from the top of a hotel staircase and trying to get it to hit the most steps on the way down.

This particular year, the game was bowling. And the Ohio State side was a man down, because my dad had once again botched his logistics and wound up on a later plane than he’d intended. This was not unusual. Logistics were, at best, a necessary annoyance in his life. The PLEASE SILENCE ALL CELL PHONES announcement before his movie.

Speaking of which...

There we were in the alley. The match already half over. To my surprise, my cell phone vibrated. I didn’t like my cell phone then (or now), and received few calls. I’d only just started carrying one. It flipped.

“Are they there?” my father whispered when I answered. In spy voice.

“Dad?” I said. Last I’d heard, he was meeting us at the hotel, much later.

“Ssssh. Move away, move away. What lane number are you on?”

I moved away and received my instructions. He’d managed to hop another flight, and now he wanted to make an entrance. Enter the alley at full sprint, and without stopping to say hello or shed his coat or—and this is key, O best beloved—change his shoes, swoop straight past the astonished assembly and grab a ball off our rack and fling a strike.

He instructed me to have a ball waiting.

There was no point in arguing. Also, why would I? “Be seeing you,” I said, Felix Leiter-style, and went off to fulfill my brief.

Eight minutes later, he came sweeping down the rows, trench coat winging open around him, hair flecked with snow, as though the snow itself had transported him there.

Only I saw him. Just as he’d planned. By the time everyone else had clocked what was happening, he was already past, ball in his hands, practically sprinting for the top of the lane. His arm swung back in what looked like unexpectedly professional form.

His left foot hit the top of the lane, slid forward and kept sliding, over the line and onto the waxed, ice-like surface of the lane itself, where no foot, and certainly no non-bowling-shoed foot, should tread.

Somehow, as he started to jackknife and tilted back, he got his right foot down, too, and it stayed down for just an instant. Like the back wheels of a plane taking off. Then he and his ball were five feet off the ground, sailing pin-ward, feet first.

For an impossible second, he hovered, fully horizontal and gliding, as though on a magic carpet. As though he were the magic carpet, because we were off the ground, too, and not just us, pretty much everyone in the place, launching as one in his direction, hands outstretched like we thought we could catch him. Mouths falling open, possibly in panic, possibly to explode into laughter. And right there, in that instant, I thought I understood something new about my father’s magic. Almost understood.

Gravity rose up and grabbed him. As gravity will. He slammed down on his back, and the back of his head. The ball from flew from his hands and landed two lanes to our right. In his version of the story, I’m sure it bowled a strike. Maybe it did. I didn’t see. I was too busy, with my uncle and brother, kneeling at the top of the lane, dragging him back to us, calling his name.

He’d had the breath knocked completely out of him. Was gulping like a hooked fish. Grabbing at the back of his skull.

And laughing. Without breath. Tears pouring down his face.

Already laughing.

I don’t know how long we stayed that way. Him laid flat, the rest of us in a semi-circle around him. He kept wincing, blinking. Jeff had started some kind of concussion protocol. Was holding up fingers, asking my father to count. By the third round of questions, he was only holding up the middle one.

“Are you okay?” we all kept asking. “Dad?” “Jer?” “Jesus.”

Mostly, we were asking that. Except when he kept breaking the mood and giggling. Every few seconds, he’d reach around back of his head, feel the wetness there. Which was melting snow. Then he’d hold up his hand to my uncle or my brother or me.

“Is this brain?” he asked.

All night, he kept asking that. The next morning, too. He wasn’t being funny at that point. Not intentionally. My father did not like being injured. Even more than most people. Partly, I think, because even his injuries got subsumed into his movie, and therefore magnified. All weekend long, he abruptly would turn the back of his skull to us and ask if we saw leakage.

He really thought there might be. But also, he knew he’d gifted us (and himself) another indelible image. Shared moment. Lifelong catchphrase.

Hence that little revelation, the thing I realized as he sailed over Rose Bowl Lanes, but processed years later.

Two years later, to be exact.

The November after he Flew by Himself, my father managed to schedule a plane at the correct time. But he missed it.

The November after that, he and I flew together. As we exited into Baggage Claim, we spotted my uncle—he was hard to miss—in full Maize and Blue regalia: pom-pom hat, matching mittens, too-long scarf that made him look like the bandit (The Wolverine, maybe) in some absurd 1930s Saturday morning serial. He was holding up a hand-lettered sign. It read:

The Saga of Jer:

2002—Airborne!!!

2003—NOT Airborne!!!

2004-- ???????????????????

And that’s when I remembered. Comprehended.

My father really did imagine his life as a movie. Lived his life as a movie, and cast everyone he met in it. But he also cast himself in everyone else’s movies. The ones he assumed the rest of us were living, too.

Bowling, breakfasts, everyday phone calls...he grabbed at it all, collected it like pebbles to fling at windows.

And then he flung them. Everywhere, all the time. In the hopes of rattling the rest of us awake, so he’d have someone to play with.

This piece captures Jerry perfectly—and is totally consistent with all that I heard about The Man Who Flew Over The Bowling Lane! So funny and sweet — brings beautiful memories for me and I am sure for our whole family! Thank you Glen for this gift. Snooze